Two minutes to midnight

In the midst of paddocks in south-central Ukraine, a tour guide and I were cramped inside an elevator at the Museum of Strategic Missile Forces, descending 30 metres into the earth to visit an Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) Unified Command Post (UCP).

When at the 11th level down inside the UCP, we stepped out into the command room. In this small space were two desks with aircraft-style seats, and an array of panels, switches and computer screens.

The officers’ seats, which looked like they were from an aircraft, were equipped with belt harnesses. These were designed to keep the staff secure during a nuclear strike. Within this cramped space, the crew of two spent their six hour shift seated at their desks, monitoring the readiness of the ICBMs sitting in their silos, and ready to initiate the launch process if the order came through.

I can only imagine your first days on the job as one of these officers, being in an heightened state of anxious mental alertness at all times, wondering if the command to launch would arrive during your shift. I wonder how long it would take before the shifts would become long and tedious, when (thankfully) nothing would happen, sitting in a sealed steel tube beneath the ground watching the minutes crawl by, with only one other person to talk to.

My guide motioned me to sit down in the commander’s seat, which was slightly raised and overlooked the subordinate officer’s desk. We were going to simulate a missile launch.

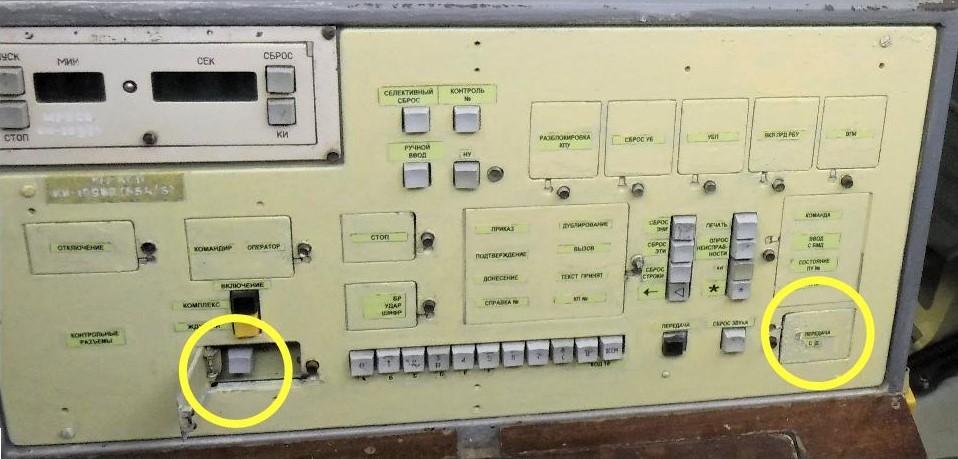

If the UCP was put onto combat status, the commander would open a stamped package to obtain a cipher code in order to activate the system, and retrieve two launch keys from a safe. At each launch desk was an identical control panel. Behind the circle on the right in the photo below is a barrel to take the launch key. The keys were inserted, and the final stage of the launch could commence. The two officers would press the button circled below left, then turn the key to the right. The turning of the keys had to be within 1.5 seconds of one another, ensuring that a single officer could not instigate a launch.

My guide and I did not have launch keys (nor live missiles in the silos, or missiles inbound from the West heralding the end of days, of course), but he instructed me to press the button after a countdown from three. Regardless of fact that our actions would not result in the launch of ICBMs, it was still a little unnerving to be pressing THE button. I wasn’t in a mock-up of a launch control centre, this was the real deal, and for many years this precise button could have created destruction on an unimaginable scale.

‘Three, two, one, go.’ We pressed the button, mimicked the turning of the key, and a large panel lit up with flashing red lights signalling that the missiles had left their silos. A harsh audio alarm sounded over and over. The guide started a video that showed what we had just initiated. It showed the launch, the ICBM’s travelling into space, their multiple guided nuclear warheads separating from the rocket, and heading back to earth. Footage of nuclear explosions followed. It may all have been a simulation, but it was still unsettling.

After we had started World War III, my guide lead me to a steel ladder, which took us down to the 12th and lowest level of the UCP.

We were in the crew room where, during a combat situation when above ground was a holocaust, the officers could survive. There were beds, food stores, cooking equipment, weapons, a television and a radio.

The 12th level could independently sustain the crew of two for 45 days. Presumably beyond this time period there would be no need for the base to operate, as the world as we know it would have ended. It was a sobering thought, to say the least.

Stepping back into the lift, my guide pointed out the massive shock absorbing arms, clearly visible in the narrow gap between the UCP and the elevator, that held the UCP in suspension within the concrete lined silo. I am standing in the bottom of the photo below, just inside the door of the UCP. My guide is in the elevator.

Squashed into the elevator, we ascended back to the top of the UCP. I followed my guide back through the corridors and steps up to the surface, where we exited via a different access point from which we had entered. From the solid steel blast door we walked out into the biting wind, and over to the top of the UCP silo from which we had just emerged. In the photo, the black circle is the concrete reinforced ‘cap’ on top of the UCP, the trailer on the right was used to transport the UCP cylinder to the site, and the ‘tipper’ on the left used to lower it into the silo

The ICBM missile base at Pervomaisk was responsible for 10 missile silos, which were located up to 13km away. One is within the museum grounds, and we walked across to the massive, 121 ton steel cover that hid, and protected, the ICBM standing in the silo beneath.

Unless under combat status, or presumably for testing / maintenance, the giant cover sits flush with the ground. If the order to launch is received, the hatch opens in an impressive 6-8 seconds. Beneath the cover is the nose section of an ICBM, showing where the rocket stood within the silo.

Walking back to the museum entrance, we passed a long line of heavy vehicles, which my guide explained was a mobile ICBM launching station. Everything required to transport, launch and control ICBMs was present in the convoy, which could set up a secret launch site anywhere, such as deep inside a remote forest.

My tour had concluded, and I thanked my guide and walked towards the exit. My visit to the Museum of Strategic Missile Forces was fascinating, illuminating, and terrifying. The brinksmanship, mistrust and misunderstanding between the east and west during the Cold War had created weapons so monstrous that offensive, defensive or erroneous launch would had spelled the end of everything.

The conclusion of the cold war pushed back the hands of the Doomsday Clock from it’s former peak of two minutes to midnight, set at the start of the nuclear arms race in 1953. Thankfully sanity prevailed, and the horrifying destructive potential of the missiles stationed amongst the paddocks at Pervomaisk, Ukraine, and innumerable other sites across the globe, was never realised.

Visit the Museum of Strategic Missile Forces here

If you liked this post, you may also enjoy Museum of Strategic Missile Forces Part I, Visiting Chernobyl Part I

Leave a Reply