‘After Mareth…our next engagement was at a place called Wadi Akarit…The Wadi…was at the end of a long flat plain dominated by mountains. I think the Djebel Roumana was one of the mountains…’ Major Peter Watson, 7th Battalion Black Watch1

After turning off the north/south road, I made my way along a baked clay track towards the beach. On my right was a wadi, steep sided and deep, dotted with palm trees and lined with scrubby vegetation. As I neared the Mediterranean, the walls of the wadi fell away, and it became a broad, shallow tidal estuary. The wind that had blown hard for three days had gone, and groups of flamingos waded the calm, shallow waters.

I switched off the bike and flicked down the side stand. After taking off my helmet, I traced the course of the wadi from where it met the sea until it disappeared somewhere on the flat coastal plain. In the distance, a series of hills broke the horizon: Djebel Roumana and Djebel Meida*.

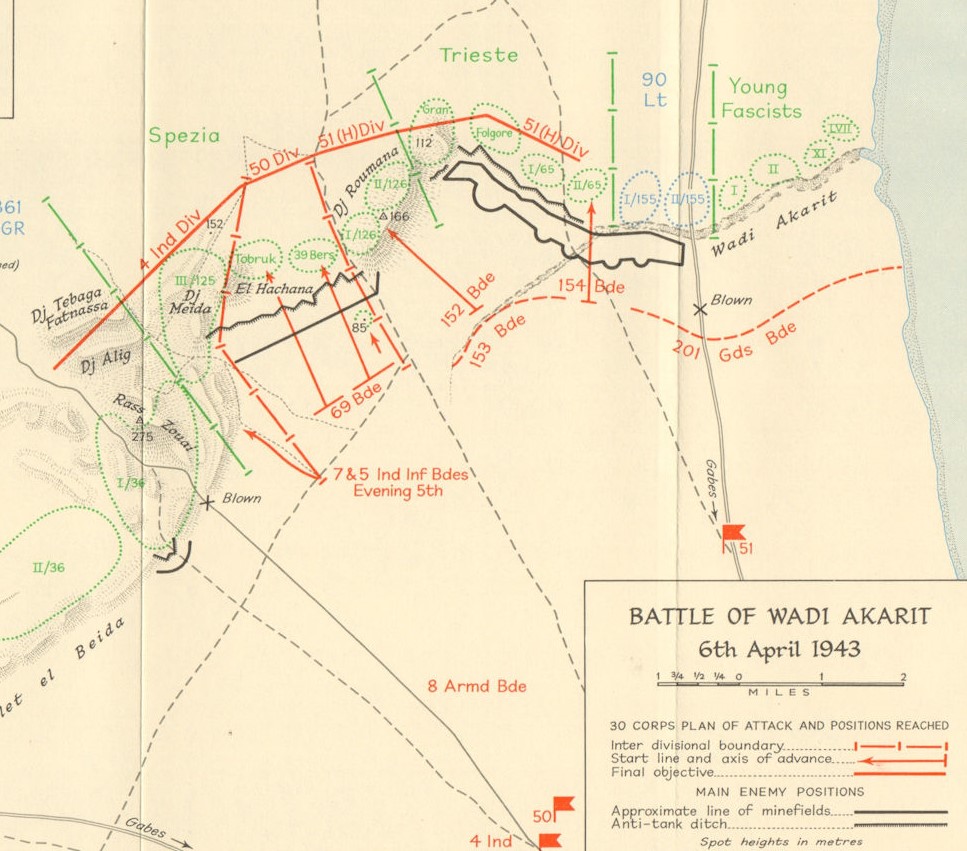

I was about 30km north of the coastal Tunisian city of Gabes, and the drainage line I had followed was Wadi Akarit. In 1943, after retreating north from the Mareth Line, the Axis forces had chosen this watercourse, and the topographic features to the west, as their defensive position from which to hold the Allied northern advance.

Using anti-tank ditches and minefields, the point where Wadi Akarit petered out on the coastal plain to the west had been linked to Djebel Roumana, where the Italians and Germans had taken up positions in the rocky hills. Another anti-tank ditch and minefield plugged the gap between Djebel Roumana and the Axis defenders at Djebel Meida to the south. Impassable salt lakes to the south-west completed the Axis line.

‘The attack was to go in as follows: the 51st Highland Brigade on the right, the 4th Indian Gurkha Division on the left, our 69th Brigade (50th Infantry Division) would attack the centre gap…‘ Corporal Bill Cheall, 6th Green Howards2

Enjoying the warm sun and cool air, I dug my lunch out of my backpack. As I ate, I watched a mob of camels lope by, their herder weaving back and forth behind the mob, urging them on when they lowered their heads to nibble at the scrub. With hunger pacified for at least a couple of hours, I got back on the bike, intending to ride the length of Wadi Akarit.

‘The battle itself took place on the 6th of April, 1943. The night prior to the battle we had taken up our…positions…Because it was going to be a daylight attack…we couldn’t take any blankets etc with us to the pre-assault area. And I remember lying on the ground, beautiful night of course, (clear) sky, stars…There we lay, teeth chattering from the cold…waiting for first light.’ Major Peter Watson, 7th Black Watch1

I made my way back along the side of the Wadi, then crossed the north/south road and picked up another track on the western side. From here I could follow the waterway across the coastal plain towards the hills. A group of kids stopped their game to watch as I approached, then gave me a friendly, if slightly confused, wave. This reaction to a stranger on an unusual looking motorcycle is common in Tunisian villages where visitors must be rare.

‘The road bridge over the Akarit Wadi, destroyed by the enemy’, 1943, Imperial War Museum (NA 1923)

‘We crossed the start line at 0400 on a lovely moonlit night. It was almost eerie. Everything was so quiet at this early hour. And then all of a sudden…our 25 pounders opened up and we moved forward at a steady walking pace.’ Corporal Bill Cheall, 6 Green Howards2

I was hoping to find some remnant of the anti-tank ditch that had been dug from the ‘end’ of Wadi Akarit to the foothills beyond. A lot of more recent earthworks had been undertaken on the flat plain, such as roads and a complex of earthen banks that delineated individual olive groves and cropping plots. After zigzagging through the area and not having any luck, I gave up and headed to the northern end of Djebel Roumana. This range of hills was the northernmost of the two ranges that held the Axis defenders in April 1943.

‘Shells began to fall a little way in front of us, then behind us, and then amongst us…some of our lads began to fall, wounded, killed, at times blown to smithereens…We felt very exposed on that flat plain…’ Corporal Bill Cheall, 6th Green Howards2

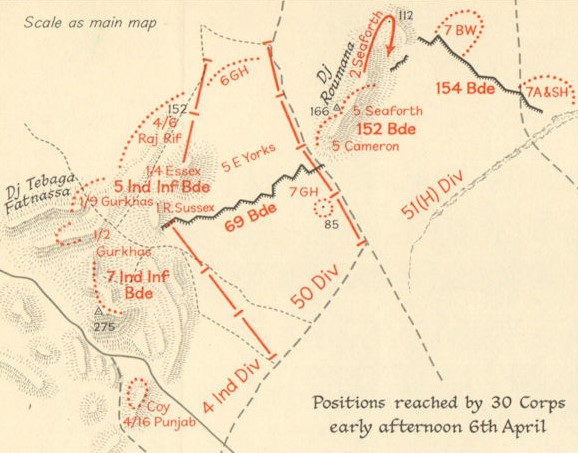

I followed a rocky track part way up the Djebel, then left the bike and continued on foot. Cresting one of the hills, I looked down over the expanse of the coastal plain, laid out to the sea. Remnants of trenches and foxholes were still clearly visible, from which I imagined the defenders watching the approaching 51st Highland Division. Shrapnel lay around the positions, jagged-edged and rusty, testimony to the battle which took place here 80 years ago.

‘Once daylight came, I lay with my glasses fixed on Roumana, but not a man could I see amongst the clouds of slate grey smoke and chestnut dust which cloaked the entire ridge as the German guns and mortars hit back. Beneath this, as I afterwards learned, there was hard fighting amongst the rocks as first one side then the other gained the crest.’ Major G. Andrews, 5th Seaforth Highlanders3

‘There was…a hill we called ‘The Pimple’ some 1000 yards back from the ditch with a razorback edge to it. And we mounted our machines guns…on the top of this ridge from which we could see over the anti tank ditch. We could see the Italian anti-tank gunners… and the infantry. And we had a wonderful shoot, and we were almost impregnable…’ Major General Peter Martin, 2nd Battalion Cheshire Regiment4

After exploring the hill tops and drainage lines I returned to the bike, and plugged in the coordinates for the second of the two main Axis anti-tank ditches dug on the Wadi Akarit battlefield. (I am very grateful to military historian and expert on Tunisia during WWII Trevor Sheehan** for supplying these and other coordinates.) This fortification linked Djebel Roumana to Djebel Meida to the south, and lay in the path of advance of the 50th Infantry Division on the 6th of April.

‘Italian dug anti-tank ditches where formidable affairs. 12 or 15 feet deep with the enemy side almost vertical. They were quite impassable to any tank. Even infantry found them difficult to cross without the use of scaling ladders.’ Sergeant Brian Moss 233 Field Company Royal Engineers2

Following the map app, I wound my way out of Djebel Roumana and turned south, following the tracks that link the small settlements lying on the eastern side of the hills. I passed ‘The Pimple’, the 85 metre tall hill just south of Djebel Roumana, then followed the gradual rise of the ground until I reached the ditch. Although shallower than when dug in 1943, it was still clear to see.

I followed the zig-zag path of the ditch to the south-west, until I could make out where it butted up against the rocky range. After seeing the natural features of the area first-hand, and the remains of the anti-tank ditch, I had a whole new understanding of what the allies had faced on April 6th.

Leaving the ditch, I made my way south until I picked up the sealed road, and turning right, rode towards the steeps cliffs that peak at Point 275. By a roadside cutting, a monument commemorated the sacrifice made by the 4th Indian Division, who had scaled this forbidding range on the night of April 5th, 1943. The south-facing panel read:

‘IN MEMORY OF THE OFFICERS, NCOs AND MEN OF THE 4th INDIAN DIVISION WHO GAVE THEIR LIVES ON THE MARETH LINE IN THE MATMATA HILLS AND IN THE HILLS AROUND THIS PASS BETWEEN MARCH 20th AND APRIL 7th 1943.’

The other sides of the monument featured the names of those killed in action.

‘…the Gurkhas had already gone into action in the dead of night in their usual way, stealthily, without any artillery support whatsoever. With their Kukris, a very sharp curved broad knife about 18 inches long…these very brave soldiers from Nepal must have put the fear of death into the enemy. On the other hand…(they) would not live long enough to be afraid, because in seconds, his decapitated head would be on the ground.’ Corporal Bill Cheall, 6th Green Howards2

Point 275 holds a series of communication towers, and an access road allows you to get close to the summit. From there, the views across the Wadi Akarit Battlefield are spectacular.

‘Most of the enemy there were Italians…It was rocky terrain and they’d stay there and fire on fixed lines probably, or if not they would just pop their head up above a rock and fire and then go to ground again. When you came up to attack them, they surrendered…And that’s what happened most of the time, we attacked and they surrendered, and we just had to pass these hundreds of Italians…sent them on their way back to our lines.’ Colonel Peter Jones, 1/9th Gurkha Rifles5

‘Prisoners coming in after the battle for the Wadi Akarit’, IWM (E 23669)

The Germans counter-attacked on our front and at Roumana…they were very brave in taking us on because they had no hope, we were too strong, and we beat off every counter attack, and by evening the Germans had decided it was a hopeless task and they retreated and went across the plain to the next position which was Enfidaville, about 40 miles to the north…’ Colonel Peter Jones, 1/9th Gurkha Rifles5

The Battle of Wadi Akarit may have been a resounding victory for the Allies, but it came at a cost of 1,289 casualties6. Three Victoria Crosses were awarded during the action.

‘By the following morning, the enemy had all gone. It was a wonderfully quick and complete battle.’ Major General Peter Martin, 2nd Battalion Cheshire Regiment4

Where the Allies advanced towards the Axis line in April 1943, today small villages and farms cover the flat coastal plain. Djebel Roumana and Djebel Meida are peaceful places, their rocky slopes visited by herders and their goats. Occasionally a stranger like me will also walk the hills, trying to imagine the chaos of noise and violence that occurred here 80 years ago.

*The higher peaks in the hills south of Djebel Roumana have individual names, however when talking to local people I was told the collective area was referred to as ‘Djebel Meida’. I will use Djebel Meida in this post for simplicity.

**On Trevor Sheehan’s website www.africanstalingrad.com you will find a link to his page on X, where there is a wealth of information about WWII in Tunisia

1Imperial War Museum, 1990, ‘Watson, Peter, Oral History‘

2Paul Cheall, 2013, ‘North Africa WW2 – The Battle of Wadi Akarit in Tunisia‘, Fighting Through Podcast

3Barnes, B.S., 2007, ‘Operation Scipio, The 8th Army at the Battle of the Wadi Akarit, 6th April 1943’, cited in ‘Major Andrews 5th Seaforth Highlanders Account of Wadi Akarit 6th April 1943’, 51st Highland Division, Museum of the Royal Regiment of Scotland

4Imperial War Museum, 1992, ‘Martin, Peter Lawrence de Carteret, Oral History‘

5Imperial War Museum, 2001, ‘Interview with Michael Peter Feltham Jones‘

Bidwell, S., 1975, ‘Wadi Akarit‘, War Monthly, Issue 12, 1975, Marshall Cavendish

If you liked this post, you may also enjoy Enfidaville Cemetery, Tunisia, and Searching For The Blockhouse, Egypt

Leave a Reply