It was a typically cold and drizzly day, with leaden clouds sitting low over the flat farmland. Approaching the speed restricted zone outside the town, I backed off the accelerator and flicked on the wipers. ‘Should be…just about…yep…here it is…’ I said out loud, despite being the only one in the car. I indicated left, slowed, and pulled off the bitumen onto the unsealed access road. Pulling up in the car park, I reached into the back seat for my raincoat and hat, then got out and looked around. Spotting the memorial, I crunched over the wet gravel, my shoulders hunched against the cold and rain.

‘This memorial is dedicated to the memory of Thames born Air Chief Marshal Sir Keith Park, Commander 11 Group during the Battle of Britain. This memorial is also dedicated to those New Zealand and other allied aircrew who fought with Sir Keith during the Battle of Britain between July and October 1940.‘

I looked out over the sodden grass runway of the airfield. The legend of the Battle of Britain was well known to us growing up in Australia. How the battered British forces had retreated from Dunkirk, and England lay vulnerable to invasion. How in the summer of 1940, the Luftwaffe had more aircraft than the RAF, and more experienced pilots to fly them. How fierce battles were fought in the skies over England and the Channel, at the cost of so many young lives. How, against the odds, the RAF had prevailed. And how the Battle of Britain pilots had become known as ‘The Few’ after Churchill’s speech of gratitude for the service and sacrifice of the British airmen.

Considering the weather, the deep green of the paddocks, a town called Thames, and the memorial to the allied airmen who saved Britain from German invasion in 1940, I could have been in England. But I was on the other side of the world, south-east of New Zealand’s capital Auckland. It was 2020, and Covid-19 had scuppered my ’round the world plans. My three week stay in Aotearoa would end up blowing out to six months. It would take the lifting of Covid travel bans, and four years of wandering, before I would visit England. And when I finally did, I went searching for The Few.

‘…the Battle of France is over. I expect the Battle of Britain is about to begin…Let us therefore brace ourselves to our duties, and so bear ourselves that if the British Empire and its Commonwealth last for a thousand years, men will still say, ‘This was their finest hour.’ Prime Minister Winston Churchill, speech at the British House of Commons, 18th June 19401

‘For the purpose of creating conditions for the final defeat of Britain, I intend continuing air and naval warfare against the English motherland in a more severe form than hitherto…The Luftwaffe will employ all forces available to eliminate the British air force as soon as possible. In the initial stages, attacks will be directed primarily against the hostile air forces and their ground service organization and supply installations…’ Führer Adolf Hitler, Directive No. 17, Führer HQ, 1st August 1940.2

When we descended below the clouds on final approach to Stanstead airport, England looked grey and gloomy. It was early summer, and sitting in my window seat I could well understand why the English travel abroad to find some holiday sun. It was a stop-start run into London on the shuttle bus, then a quick train ride to Hendon Central. After a short walk in the early evening gloom I arrived at my accommodation. The following day I would begin my journey into the history of the Battle of Britain at the Royal Air Force Museum London, housed at the former Hendon Aerodrome.

Hendon is itself part of the Battle of Britain story. According to the RAF Museum, ‘a number of fighter squadrons used the airfield for short periods’ during the Battle. It also suffered bombing raids from August 1940, as the Luftwaffe carried out Hitler’s Directive No. 173. The land that was once RAF Hendon is now shared by a housing estate, the Hendon Police College, and the RAF Museum.

Next day, I entered the Museum grounds and passed Hendon’s two impressive ‘gate guardians’: full-sized replicas of both a Spitfire and Hurricane, mounted on poles as if in flight. Admission to the museum is free, and after walking around the gargantuan Short Sunderland flying boat in the entry hall I headed straight for Hangars 3, 4 and 5 (which are really just one mega-hangar). I have a pathological need to see, read and photograph everything when I visit an aviation museum, which compels me to arrive at opening time and stay until I’m chased out by the cleaners. Having only two days to explore the vast museum at Hendon, I thought I’d better head straight for the Battle of Britain exhibits first. Arriving on a weekday morning, I pretty much had the place to myself.

The centrepiece of the Museum’s Battle of Britain display was the ‘Fighter Four’: three aircraft that are synonymous with the Battle, and one that most definitely isn’t. WWII-era aircraft are, by their nature, rare birds. Museum exhibits are often aircraft that were built late in the war and never saw service. However not only are Hendon’s Fighter Four all WWII veterans, they are quite possibly all genuine Battle of Britain survivors too.

Although the Spitfire is considered the star of the Battle of Britain, it was the Hurricane that did the heavy lifting.

Hurricanes destroyed the majority of Luftwaffe aircraft during the Battle, and equipped more operational squadrons than its more glamourous ally.4 RAF Museum Hendon’s Hurricane is a Mk I, serial number P2617. After taking part in the air war over France, this aircraft returned to England in May 1940, and was flown out of RAF Tangmere (West Sussex) and RAF Prestwick (South Ayrshire, Scotland) during the Battle of Britain.4,5

Beside the Hurricane was Spitfire X4590, flown by Pilot Officer Sydney Hill, 609 Squadron, during the Battle.

P/O Hill is credited with a ‘shared’ after the destruction of a Junkers Ju88 with fellow 609 Squadron pilot Flight Lieutenant Frank Howell DFC on October 21st.6

Pilot Officer Sydney Jenkyn Hill was born in Dorset. After leaving school he studied metallurgy, before joining the RAF in 1940. P/O Hill served with 609 Squadron at Middle Wallop during the Battle of Britain. He was killed on 18th June 1941, aged 23, when his Spitfire crashed near Dover after combat with Luftwaffe fighters over Cap Gris Nez, France.7

Born in London, Flight Lieutenant Frank Jonathan Howell DFC joined the RAF before the outbreak of the the Second World War. F/L Howell flew with 609 Squadron during the Battle of Britain and was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross on 25th October 1940. Surviving the war, he was killed in an accident whilst still serving in the RAF, aged 36.8

Across a walkway stood an example of the Luftwaffe’s premier fighter during the Battle, the Messerschmitt Bf 109.

On 27th November, 1940, this aircraft was being piloted by 21 year old Leutnant Wolfgang Teumer, a veteran of 80 sorties against England. After sustaining battle damage over the Thames estuary (inflicted by 66 Squadron Spitfire pilot Flight Lieutenant George Christie DFC), Teumer belly-landed the aircraft at RAF Manston. Teumer’s Bf 109 was repaired to airworthy status using parts from several other machines, and subsequently used for testing by the RAF.9

Flight Officer George Patterson Christie DFC was born in Montreal, Canada, and joined the RAF in 1937. He served with 242 and 66 Squadron during the Battle of Britain, and survived a forced landing and being shot down on two consecutive days. F/O Christie was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross on 25th August 1940. He was killed in a flying accident in Canada in 1941, aged 23.10

Hendon’s Bf 109 is therefore not entirely the original Messerschmitt works number 4101. And considering that the Battle of Britain officially began on 10th July and ended on 31st October11, was not shot down during the Battle. However, it is likely that both Teumer, with his service record, and 4101 which was operational by September 1940, are indeed Battle of Britain veterans.

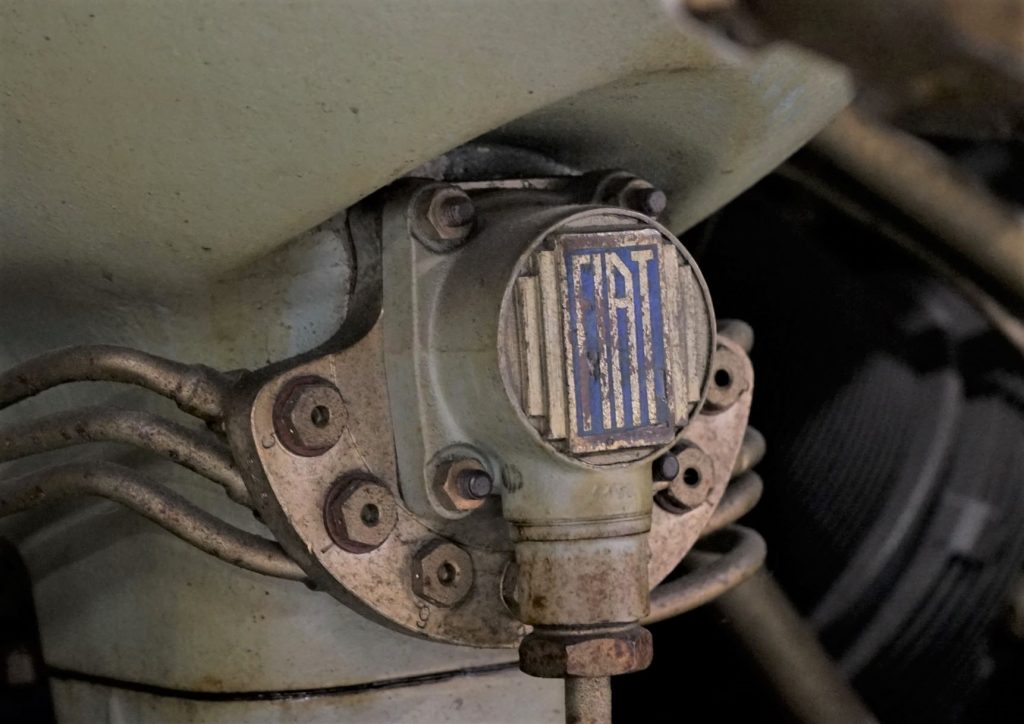

The fourth fighter on display was this Regia Aeronautica Fiat CR.42 Falco MM5701. I have to admit I had no idea the Italians were involved in the Battle of Britain.

I discovered that it was a political decision, rather than an operational requirement, that saw the creation of the ‘Corpo Aero Italiano’ to ‘support’ the Luftwaffe in actions over Britain. It would not be until the 24th October, the last week of the Battle of Britain, that the Corpo would conduct its first sortie.12

The Museum states that Falco MM5701 was part of Corpo Aero Italiano in October 194013, and therefore may have flown in the second Italian sortie on the 29th which involved Fiat CR.42s.14 These were the only two operations conduction by the Corpo Aero Italiano within the official dates of the Battle of Britain.

During a later sortie, Sergente Pilota Pietro Salvadori forced landed MM5701 with engine trouble at Orford Ness, Suffolk, on 11th November 194012*. Like Leutnant Teumer’s Bf 109, after it’s arrival in England Salvadori’s aircraft was also used by the RAF for testing.12

Similar to Teumer, the Italian had been forced down after the Battle of Britain had concluded. When producing official reports I can understand the need to bookmark the Battle with specific dates, but I expect in reality the start and finish of the Battle of Britain was a little more hazy.

My time spent quietly inspecting the Battle of Britain Fighter Four display was shattered when what seemed like all of London’s primary school children came pouring through the door. I made a hasty retreat further into the hangar, and found a particularly rare WWII survivor.

Of the over 6000 Messerschmitt Bf 110’s built, only two complete aircraft remain.

Although Hendon’s example is a night-fighter variant produced later in the war, the Bf 110 was used by the Luftwaffe during the Battle of Britain.

Bf 110s flying sorties over Britain in the summer of 1940 were out-performed and out-gunned by their RAF fighter opponents.15

With the kids closing in again, I scarpered to a quiet corner of the hangar where I found two more German aircraft, the types of which were flown by the Luftwaffe during the Battle of Britain.

Only two complete Junkers JU87 Stuka aircraft are displayed anywhere in the world; one at Hendon and the other in the US. Hendon’s aircraft is a later variant than that used in the Battle.

Like the Bf 110, the Stuka also proved vulnerable to the more manoeuvrable Hurricanes and Spitfires.16

Opposite the Junkers JU87 was an example of the Luftwaffe’s main bomber used during the Battle of Britain, the Heinkel He 111.

Hendon’s aircraft was built later in the war and designed for paratroop operations.17

Having spent many hours and taken a zillion photos, I left the RAF Museum Hendon in the late afternoon. It had been a fascinating start to my Battle of Britain journey; I had seen authentic aircraft, and been introduced to a number of the pilots that had fought in the summer of 1940.

Although I would return to Hendon the following day to spend some time amongst the many other exhibits, the next stop on my search for The Few would be a small grass airstrip in Kent…

A few tips for visiting the Royal Air Force Museum, Hendon, London

- The Museum is big, really big, displaying aircraft from all eras. If you have more than a passing interest in aviation, you’re going to need more than a day.

- As mentioned above I’m probably an extreme case, but I could easily have filled three days at Hendon. Splitting your visit over a few days also avoids getting overwhelmed when trying to take in too much information in one hit

- Entrance to the Museum is free, but please consider making a donation to this amazing place

- For opening hours and up to date information visit the RAF Museum London website here

*RAF Museum information states that ‘When interrogated by the British, Salvadori commented that he was happy to be out of the war, was dissatisfied with the Italian officers, and didn’t like Belgian weather, the Germans, or their food!’10

1National Churchill Museum, 2024, Their Finest Hour, 1940

2Hitler, A., 1940, ‘Directive No. 17 For the Conduct of Naval and Air Warfare Against England‘

3Royal Air Force Museum, 2020, ‘Hendon the cradle of aviation’

4Hawker Hurricane Mk 1 information panel, Royal Air Force Museum Hendon, London

5Simpson, A., 2015, ‘Hawker Hurricane Mk. 1 P2617/8373M‘, Royal Air Force Museum, London

6Simpson, A., 2013, ‘Spitfire I X4590/8384M‘, Royal Air Force Museum, London

7The Battle of Britain London Monument, 2007, ‘The Airman’s Stories – P/O S J Hill‘

8The Battle of Britain London Monument, 2007, ‘The Airman’s Stories – F/Lt. F J Howell‘

9Saunders, A., 2020, ‘Anatomy of an ‘Emil‘, Iron Cross, Issue 6

10The Battle of Britain London Monument, 2007, ‘The Airman’s Stories – F/O G P Christie‘

11Royal Air Force Museum, 2020, ‘Introduction to the Phases of the Battle of Britain‘

12Simpson, A, 2012, ‘Fiat CR42 ‘Falco’ MM5701/8468M‘, Royal Air Force Museum, London.

13Fiat CR.42 Falco information panel, Royal Air Force Museum Hendon, London

14Gustavsson, H., 2022, ‘The Falco and Regia Aeronautica in the Battle of Britain’, Håkans aviation page

15Webb, N. A., 2024, ‘Battle of Britain 1940.com – Messerschmitt Bf 110‘

16Royal Air Force Museum, 2020, ‘Junkers JU87G-2‘

17Heinkel He 111H-20 information panel, Royal Air Force Museum Hendon, London

Spitfire silhouette sourced from Bob Comix

If you enjoyed this post, you may also like Visiting Gallipoli, Diving the SS Thistlegorm

Leave a Reply