‘He fell fighting to end wars. Let his efforts be not in vain’

An afternoon sea breeze is blowing, shaking the scant grasses that struggle up between the coarse white gravel. I am alone, and far enough from the major highway that the only sounds I hear are natural. Before me stands the Australian War Memorial, near the entrance to the El Alamein War Cemetery, glaring white in the early afternoon sun. On one side of the monument, carved into a block of red granite are the words:

‘The Australian memorial to honour the participation of the Ninth Australian Division and its supporting arms and services in the battles of the El Alamein campaign July – November 1942’

On the other: ‘We will remember them’.

The Ninth Australian Division were the legendary ‘Rats of Tobruk’, who held out in the seaside town for 242 desperate days whilst enduring attacks from both land and air. After the siege was lifted, the Ninth spent a month in Palestine, then after further training in Syria, returned to the Western Desert. They were to fight in a pivotal battle that changed the outcome of the war in North Africa, and arguably across the European theatre. As a young bloke, I was fortunate to meet a former member of the Ninth Australian Division, an artilleryman, and to have an association and friendship with him over many years.

Lieutenant-General Bernard Montgomery, the commander of the Allied forces, had decreed that there would be no retreat from El Alamein. His counterpart, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, was making a do or die attempt to break the Allied lines and reach Alexandria. The final battle of El Alamein was desperate and fierce, and would cost a staggering 13,800 lives.

My old friend, in a newspaper interview, described the opening artillery salvo that signaled the start of El Alamein’s final battle: ‘It was murderous. There was something like 800 or 1,000 guns opened up at the one time. It looked just like a whole lot of glow worms had turned up, and the sky was alight… Even as the shells are coming in, you don’t knock off, you just keep going.’

In addition to the artillery, tanks were a central part of the battles at El Alamein. ‘When (an armour-piercing) shell hits tanks, it’s horrendous. There were blokes jumping out of them on fire, and the shells are whizzing around inside the tank, and you just had to put the tin hat on, I suppose.’

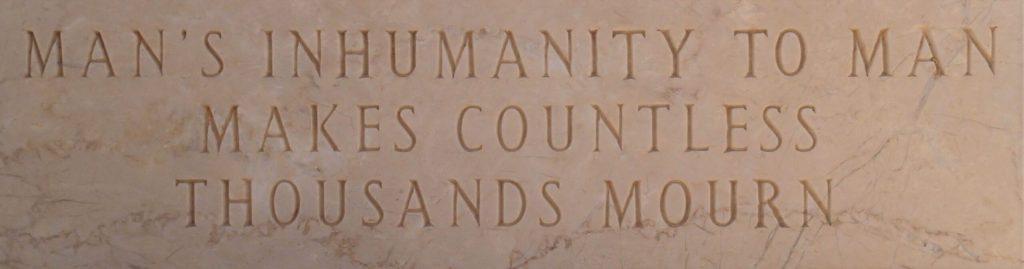

I walk down the path and through the entrance to the cemetery, arriving in the cool shade of the memorial’s arched, open hallway.

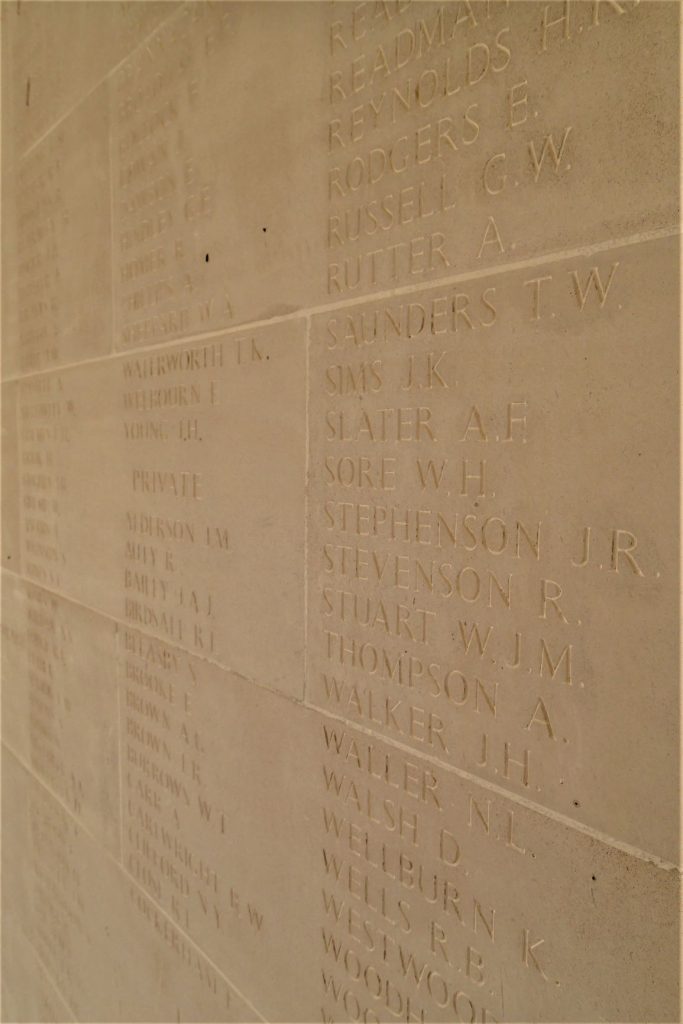

The cost of the battles of El Alamein and the wider North African conflict is carved into the walls; an honour roll of those lost from the Allied nations, including Britain, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, South Africa, Greece, India, and France (Free French).

I run my eyes down the list, whispering those with a familiar surname, or perhaps when repeated names suggest the loss of brothers. Walking slowly through the arched passage the names seem to go on forever.

Turning from the walls, I walk out into the bright sun, towards the cemetery’s expanse of graves.

Wattles and gums grow beside the Australian graves, providing a little shade from the desert sun. With respect to those lost, my friend is quoted as saying ‘…to shed a tear is not a disgrace in my book’. As I walk down row upon row of headstones, I certainly have tears in my eyes.

Some headstones have familiar epitaphs: ‘Greater love hath no man, he gave his life for his friends’; ‘Lest we forget’; and for those who could not be identified ‘Known to God’. Others are acutely personal. Twenty-five year old W.A.I. Gunton’s reads ‘Our brave boy, forever in our thoughts, loved by all, Mother’. Private J. Davies’ epitaph is ‘Rest in peace dear Jackie, Mother and Edie’. For Nineteen year old L.E. Penney ‘Our brave young hero, those that loved you will never forget’ and for A.B. Lange ‘His duty nobly done, our darling Bernie’. The title of this post is taken from another headstone at El Alamein. Some graves mention the soldier’s home; Australian towns connected forever to a dusty, sunburnt place far away on the other side of the world.

My old friend, R.J.K Semple OAM BEM, veteran of Tobruk, El Alamein, and then the jungle war in New Guinea, passed away last year at the age of 99. I think of him as I stand amongst the graves, some of which hold his friends lost during the battles of El Alamein. I will think of him again this Anzac Day.

Lest We Forget.

Learn more about the El Alamein War Cemetery here

If you enjoyed this post, you may also like Searching for the Blockhouse Part I, Part II

Leave a Reply