Suspicion, Surveillance and Subjugation

‘State security is the sharp and dear weapon of our Party, because it protects the interests of the people and our socialist State against internal and external enemies.’ Enver Hoxha

After World War Two, Albania was ruled by a communist dictatorship, lead by former wartime resistance fighter Enver Hoxha. After taking control, Hoxha wasted no time in building a terrifying state security apparatus that imprisoned the people of Albania within their nation’s borders, and sought to control all aspects of their lives.

My first day in Tirana, the capital city of Albania, was cold and wet. From the window of my apartment I could see the trees hanging heavy with rain, and clouds sitting low over the hills which border the city to the east. After pulling on my wet weather gear, I headed out into the street, joining the jostling line of people heading to their jobs in the CBD. After a short walk I arrived at my destination, the mysteriously named ‘House of Leaves’.

Behind the head-high wall stood a blocky, two-story building, with ivy scaling the shabby walls. After buying my ticket from the office at the gate, I walked up the steps to the shelter of the building’s entrance porch, relieved to be out of the rain.

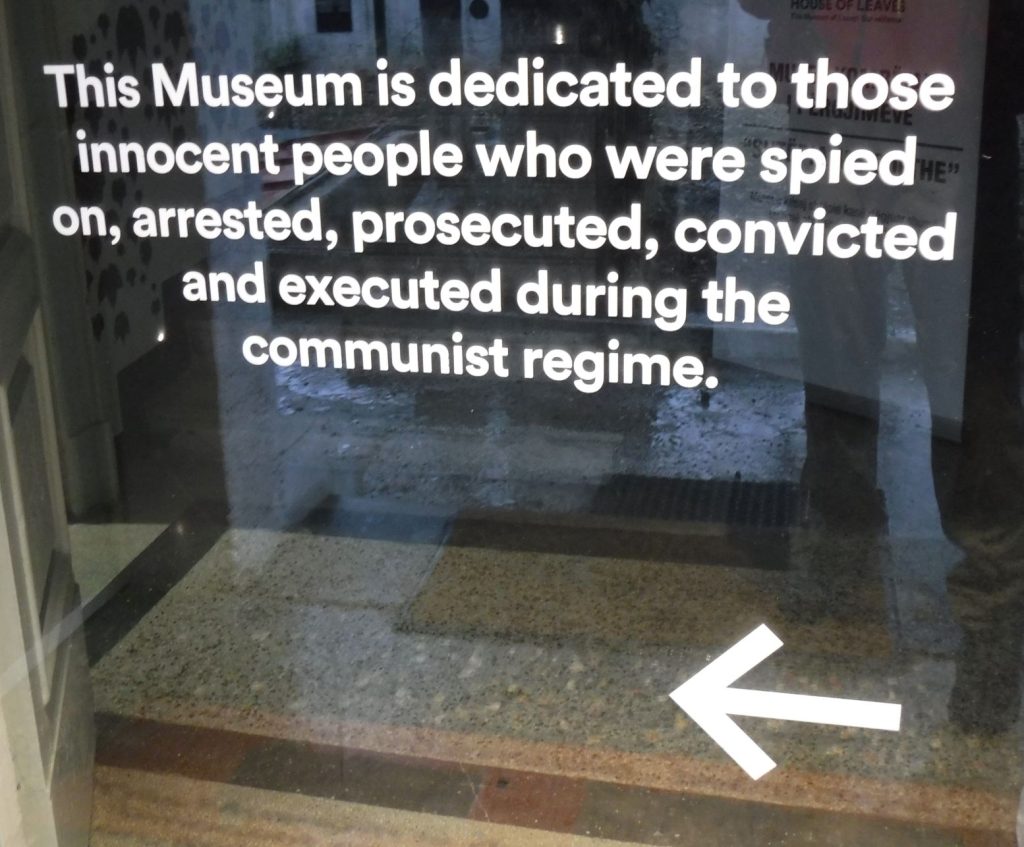

After removing my rain jacket and shaking off the worst of the water, I tucked it into my bag and entered the building. I have to admit to a sense of trepidation; the sign on the door, what I had already found out about the House of Leaves, and the appropriately gloomy weather all contributed to my unease. A staff member checked my ticket and informed me that photographing the exhibits was not permitted.

The building that became Hoxha’s House of Leaves was originally a private obstetrics clinic. During the German occupation of Albania during World War II the Gestapo took over the premises, and what were once wards and treatment rooms became places that inflicted suffering rather than alleviated it. After the war, the House of Leaves – so named for the thick vegetation that shrouded the building in secrecy – became the ‘nerve-centre’ of Albania’s Directorate of State Security, known as the Sigurimi.

The first room I entered set a grim tone for my visit to the Museum. Continuing the mistreatment of prisoners suffered under the Nazis, the Sigurimi would torture ‘enemies of the State’ within the House of Leaves. Information panels on the walls featured line drawings of some of the techniques used by the Sigurimi during the interrogation of prisoners.

‘There is no concession or mercy to the enemy nor any fear of mistake, one is never mistaken if he is tough on class enemy.’ Enver Hoxha

The House of Leaves included a display of promotional posters for feature films made by Hoxha’s regime. These fictional films told stories of action and adventure, where internal and external threats to Albania were defeated by the all-powerful State. The posters show strong-jawed and grim-faced heroes determined to protect the people from ‘enemies and saboteurs‘.

In another room, a row of monitors showed State-produced documentaries. I watched the black and white footage of smiling people walking in the summer sunshine. The Museum information explained that Albanians appearing in the films were ‘instructed to appear happy and well dressed. The interiors of private homes were manipulated to represent an affluence that was pure fiction, and to hide the poverty widespread under the regime.‘

One of the most striking displays within the museum was a room containing an enormous collection of surveillance equipment. On a large table in the middle of the room were tape recorders of all shapes and sizes, microphones, bugs, still and video cameras, telephoto lenses, computer monitors and other gadgetry used to monitor the conversations, actions and movements of Albanians. As I read the information provided on each item, one in particular caught my eye. It was a 1975 ‘Realistic’ brand ‘Model Pro 30 radio receiver-transmitter’ (a ‘walkie-talkie’). Part of the item’s description was ‘Made in Australia’. Behind the table was a wall covered with row upon row of tape recording decks.

As the House of Leaves Museum stated, ‘The right to privacy at the level of the individual citizen was not recognised by the communist regime…At the level of the family the state inserted itself into private life…exercising the right to know and decide everything with respect to a citizen’s life. The use of microphones to eavesdrop on private conversations, an unrestricted practice during the communist regime, was just one of the many tactics of the State intervention… and if an individual was declared an enemy of the state the curse was cast upon the entire family‘.

The sourcing of electronic equipment from various countries tracked Albania’s increasingly paranoid withdrawal from the Communist brotherhood of nations into an isolated State. The Museum displays explained that Initially, materiel was bought from the Soviet Union, but after splitting from the Warsaw Pact countries in 1961, Albania turned to China. When relations soured with China in the second half of the 1970s, and Albania announced that it was the only true socialist state, technical equipment was ‘purchased with hard currency from places like Austria, Switzerland and Japan‘. And Australia, apparently.

‘The information service is the observing eye, so that the normal and free development of people cannot be blocked by the dark, unpopular forces… Our information service…will be the faithful and silent guardian of the people.’ Enver Hoxha

I entered a small room where a short film loop was playing, whose soundtrack was a muffled burble of recorded voices. The development of tiny listening devices was undertaken in the labs of the Sigurimi, and resulted in the ‘A1 transmitter’ or ‘bug’. An example of this was on display; a just over 2cm long tube of electronics that could be hidden away in just about anything. It reminded me of an old-style automotive glass tube fuse. A case of drills and cutting implements used to install the bugs was shown, and also a selection of items into which the bugs were placed: kitchen condiment dispensers, the heels of shoes, items of clothing, books, ornaments, walking sticks, and electronic equipment. It was the stuff of pop culture spy movies, except this was deadly serious. The recorded conversation accompanying the short film loop was authentic, and used to incriminate a woman who was subsequently executed by the State.

Moving through the House of Leaves, I found a small, red-lit room set up as a photographic dark room. It had a distinctly spooky feel. Photographs were pegged to string lines as if drying, and equipment used for processing and enlarging photographs was shown. Surveilling and photographing Albanians suspected of posing a threat to the State was an integral part of Sigurimi activity. Beside the dark room, a range of task-specific espionage equipment was displayed, including a ‘device for squeezing letters’, which was ‘used to squeeze the letters to discover hidden inks in letter correspondence‘.

A particularly compelling display within the Museum was a room lined with black and white portraits depicting civilians on trial. Standing in a timber dock, some of the individuals are caught in moments of speech, their hands gesticulating, mouths open and eyes wide. Others stand with expressions of anxiety, fear or resignation. Some photos feature a panel of men dressed in military uniforms, who presumably hold the fate of the defendants in their hands. The next room conveyed the results of these trials, its black walls covered in names printed in small font. The State convicted and imprisoned 14,359 of its own citizens during the communist era, and executed 5,502.

I entered another room where a video was playing, showing footage of ladies with 60s hairdos, purportedly smugglers and black-marketeers, and cars leaving what appeared to be a foreign embassy. Information provided explained the role of the Sigurimi in identifying the ‘external threat’ posed by foreign nationals and diplomats. Foreign embassies were a focus for State surveillance, and city hotels were bugged to spy upon visitors to Albania.

After spending several hours exploring the Museum, I wound my way down the stairs to the exit of the building. It was still raining, so I put my wet weather gear back on and pushed out into the cold. Visiting the House of Leaves had been a fascinating, astonishing and frightening experience; a confronting introduction to the troubled history of 21st century Albania.

For a few official photos from inside the House of Leaves click here

If you liked this post you may also enjoy Red Flat, Museum of Strategic Missile Forces

Leave a Reply