Secrets hidden beneath the forest

I was doing some research into things to do in and around Leipzig, Germany, and came across the Stasi Bunker Museum in the nearby town of Machern. This unique museum is only open on the last weekend of every month, which just happened to be when I was visiting. Thankful for this stroke of luck, I jumped on a Sunday train at Leipzig’s main railway station for the half-hour journey to Machern.

Being mid-2022, Covid-19 seemed to have been largely forgotten, except on the German rail network, where masks were still compulsory for passengers. After having taken my mask out of my pocket the previous night to wash it, I had forgotten to bring it with me. I hoped it wouldn’t be a problem. It was.

I got thrown off the train by a barely 20-year old Deutsche Bahn employee who could not be persuaded to allow a maskless visitor to her country to remain on board for another 10 minutes. A cascade of fuck-ups followed, including being unable to find a shop to buy a mask, catching the wrong service twice and ending up at the wrong destination twice, and having the train that would get me back onto the right line cancelled. After much frustration and frequent coarse language, I finally disembarked at Machern, after having been literally ten minutes from the station two hours earlier.

None of this would have mattered if the museum wasn’t open two days a month, and closing in an hour and a half. But it was, and it was, so I hurried along the 30 minute walk from the station. I eventually turned up at a very ordinary looking gate in front of a very ordinary looking property.

Leipzig and Machern are in the German state of Saxony, which was part of the German Democratic Republic (DDR or ‘East Germany’) when the nation was split after World War Two. During the existence of the DDR (1949-1990) the Ministry of State Security, or Stasi, was tasked with identifying and countering both internal and external threats to the socialist state. Like policing in most autocratic societies, it did so by seeking to control all aspects of the lives of the people. The DDR was divided into 15 districts, each with a branch of Stasi administration.

In 1967 it was decided that an emergency command centre would be built for each district, remote from the Stasi administration centres which were located in major cities. Fifteen secret bunker complexes were constructed across the DDR, designed to withstand nuclear and chemical weapons, and permit the Stasi to continue to function during such an attack. I had just arrived at the Leipzig District’s bunker, the last Stasi bunker preserved in its entirety, located within a 5.2 hectare area just outside Machern.

I entered the gate and made my way to the modest building beyond. This was formerly the bunker commander’s residence, which now houses the ticket office and a gallery space.

The volunteer staffer explained the layout of the site, and gave me directions to follow the path to the ‘big shed’.

All weather access

I walked deeper into the property, which looked a bit like a council works depot, with various small buildings scattered through the leafy grounds. During its operational years, the property was ‘…officially a holiday camp for employees of the people-owned company for water supply and sewerage treatment Liepzig’.*

I came across a big shed, which looked like a some sort of storage or maintenance facility. It was the biggest shed around, so I approached the single open door and found a small sign saying ‘Engang zum bunker‘. It all looked very low key and ordinary.

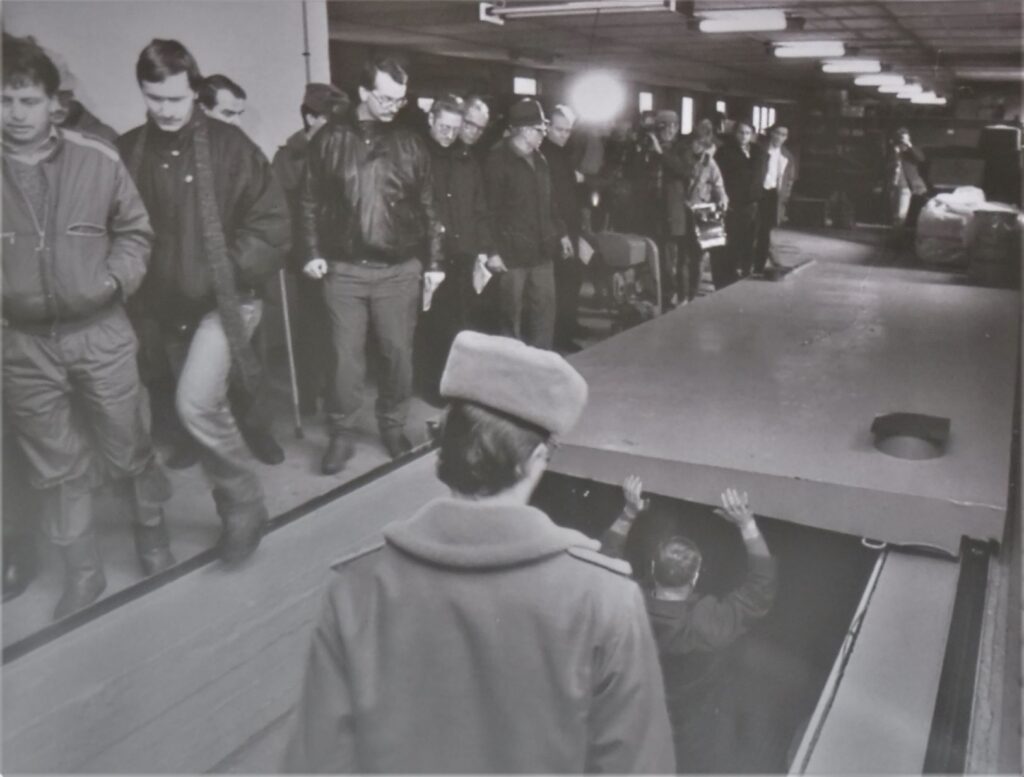

Just inside the door, a set of steep concrete steps leading downwards revealed the building’s secret purpose (see photo above under title). A huge concrete slab on rails sat above the steps, ready to roll into place and seal off the complex in case of attack. I was met by a museum staff member, who very modestly apologised for her perfectly adequate English skills. She gave me several laminated pages of notes in English, and sat me down in front of a short slideshow which outlined the history of the bunker. The photo below is from the slideshow, where members of the public are touring the facility shortly after the dissolution of the DDR in 1989.

I appeared to be the only visitor there, and after the slideshow my guide took me down the steps for a personal tour of the bunker system. At the end of a corridor, she heaved open an airlock door and we stepped back to a time when the Stasi terrorised the GDR.

Spooky

Built between 1969 and 1972, the facility is a 1500 square metre warren of concrete passageways and long, narrow rooms. The bunker was equipped to allow 100 officers to live and operate underground for seven days in the event of a nuclear attack. I guess after seven days they were just going to wing it. The site had a distinctly Marie Celeste feel to it, and you got the feeling the Stasi could just turn up any minute, slide the concrete lid shut, and get on with business.

Beyond the airlocks and decontamination area we entered the ‘clean zone’, where a control desk with a diagram of the complex was situated.

From this position the bunker’s technical commander could control the facilities essential services.

Games of Pacman helped pass the time

Opposite the control desk, the office of the Liepzig Stasi Commander had a distinctly austere, Eastern Bloc feel.

Ah the good old days, when if you wanted two phone lines, you had to have two phones. And if you wanted three lines, well then you had to have three phones. The Stasi Commander probably would have added even more phones to his desk if not for his penchant for voluminous lampshades

Moving deeper into the bunker, we reached a room containing ventilation equipment. A series of filtration systems could be employed if the outside air was contaminated.

If the radioactive or chemical shit hit the fan, literally, then the complex could be completely sealed from the external environment. In such a case, oxygen cylinders would be deployed.

No smoking

If there was a problem with the primary motor which ran the ventilation system, a backup could be used. If that failed, air could be pumped around manually by some poor bastard peddling like buggery on a stationary bike.

‘Righto boys, if there are no volunteers we’re gonna have to draw straws’

In addition to the oxygen canisters, each room featured a chemical oxygen maker. My guide explained that these were Russian, and were standard equipment on Russian submarines.

Doesn’t really inspire confidence, does it…

We passed a water filtration plant, and then an area holding telecommunications equipment. Clearly there would be no point in having a command bunker without being able to issue any commands, and my guide told me the equipment was state of the art in its time. The sleeping quarters were basic, but hey, this place ain’t a holiday camp.

After viewing the kitchen and dining areas, and the bunker’s medical facilities, we reached another set of airlock doors leading to the second entry/exit point.

We left the ‘clean zone’, and climbed another set of steps up to the ‘big shed’. Back on the surface, in that very ordinary building, it was hard to believe the fully-equipped, subterranean submarine was buried beneath my feet.

I thanked my guide and headed out into the warm summer’s afternoon.

If you’re going to keep the bad stuff out, you’re going to need some serious doors

Walking around the neatly mowed lawns surrounding the building, I found information panels explaining various steel fittings protruding from the ground.

These included an emergency exit, radio antenna, air intakes and this well shaft.

Clearly they would have kept the mower in the shed during the the bunker’s operational years.

I had certainly been lucky that the Stasi Bunker Museum just happened to be open when I visited Leipzig. Despite the Deuthsche Bahn staffer’s effort to, ahem, de-rail my visit (oh come on that’s probably not even the worst gag you’ve heard today), I made it and found the Museum fascinating. If you’re planning a trip to Leipzig, and you’re interested in Cold War history, make sure you are there on the last weekend of a month.

*Quote from Stasi Bunker Museum information brochure

For more about the Stasi Bunker Museum click here

If you enjoyed this post, you may also like Beneath the Streets of Prague, Museum of Strategic Missile Forces