The Cold War Museum

I find Cold War history frightening and fascinating, so when I found out there was a museum in a nuclear bunker right under the city centre of Prague, I promptly booked myself a tour.

The day of my visit I caught the tram into town, then made my way towards Wenceslas Square.

The meeting point for the tour of The Cold War Museum was the reception of the Jalta Hotel, beneath which lies a labyrinth of tunnels and rooms that remained secret until 1989.

Ritzy

After a short wait in the hotel lobby with eight other visitors, our guide appeared dressed in a communist-era Czechoslovakian military uniform. A jovial and talkative young bloke, Jacob gave us a rundown of what to expect on our tour.

‘Welcome to the Jalta Hotel comrade! I trust you will have a pleasant stay…’

Then, just like in the opening credits of Get Smart, we entered the hotel lift, the doors closed, and down we went.

‘Chief, I demand the cone of silence’

After descending we exited the lift and went down a couple of flights of stairs.

Jacob gathered us in front of a blast door, and explained that the top secret complex was designed to accommodate the Communist Party hierarchy in case of a nuclear strike.

‘Please, there is nothing to worry about. We just want to ask you a few questions…’

Presumably, the decision was made to include a bunker as part of the construction of the Jalta Hotel (which was completed in 1958) as it was a central location for Czechoslovakian Communist Party leaders living in Prague.

Further, high ranking officials visiting from other Eastern Bloc countries would be invited to stay at the hotel during their time in the capital.

‘Quick! Come inside where it’s safe…ish’

Beneath the city, the bunker could shelter around 150 people during a nuclear attack, whilst presumably most of the rest of the citizens were incinerated. Having the bunker beneath a hotel also proved beneficial to the regime’s clandestine operations, but more on that later.

After passing through a blast door, we arrived at the first stop on our tour: a room kitted out as an operating theatre. Jacob told us that although the bunker had been equipped with such a facility, this particular room was not the original location of the medical room.

In fact, the precise use of many of the rooms inside the bunker remains unknown, as most were empty by the time the complex was uncovered. At the end of the medical room was a small open hatch, which Jacob explained was the entrance to an escape route to the surface. Apparently after a short length of tunnel there is a ladder leading up to an exit amongst some shrubs in the middle Wenceslas Square.

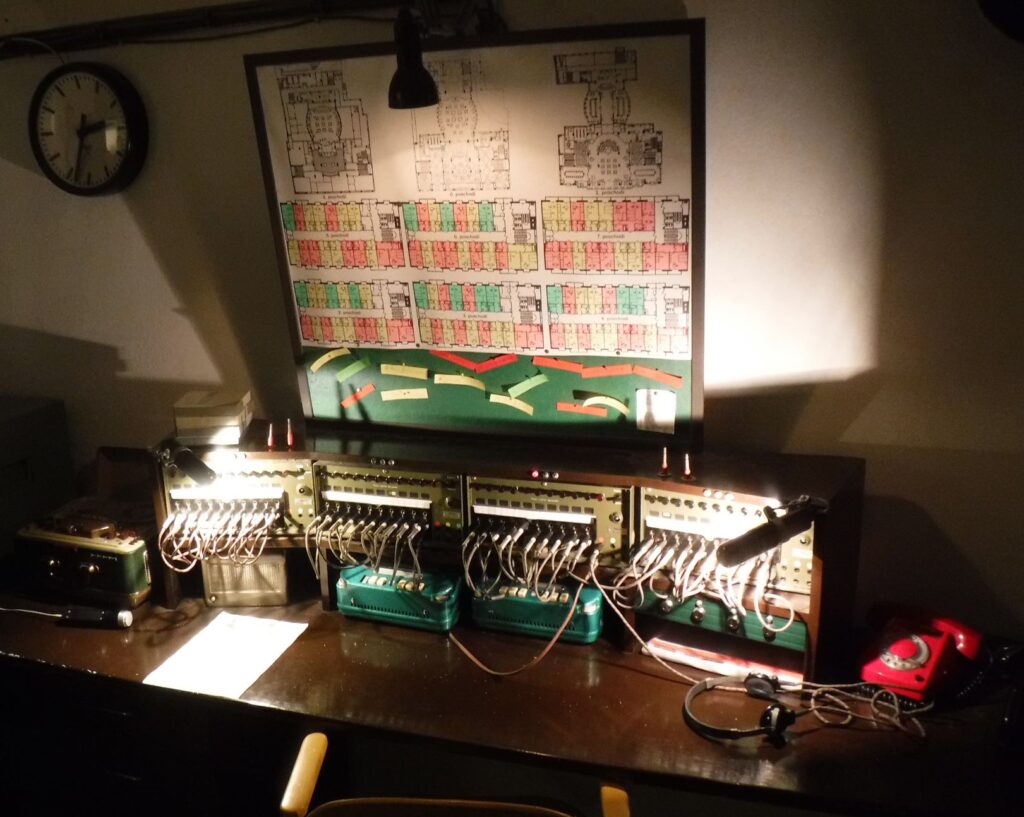

One area within the bunker whose role had been identified was the ‘War Room’. Our guide lead us inside where communications equipment sat on the desks, and a map covered much of one wall.

Just another day at the office

Jacob told us that the map displayed the defensive and offensive assets, such as missile sites and airfields, located in Czechoslovakia in 1985. Weapons facilities were colour-coded, with concentric circles showing their effective range. A line of red lights on the map marked the ‘Iron Curtain’ along the border with Austria and the former West Germany.

After a short stop at an armoury to check out some police/military weaponry, Jacob took us to a room that had been set up to represent a Czechoslovakian border checkpoint. He showed us Communist-era banknotes, and explained that a limit was placed on the amount of cash an individual could take on a trip out of the country. This was to dissuade people from packing their life savings to start a new life outside their homeland’s socialist utopia.

We moved on to what Jacob called the ‘Interrogation Room’, where he showed us a mock-up display which included authentic police truncheons and riot control gear. Peaceful protests against the communist dictatorship, which were reported as ‘riots’ in the state-controlled press, were ‘subdued’ using such equipment. Jacob told us a story about his grandfather, who was arrested for attending an anti-government rally when he was 16 years old. As was typical of the time, the government took a dim view of such activities, and the boy’s sins were compounded as he was from a family of ‘Kulaks’; small landholders considered ‘class enemies’. For his attendance at the rally, Jacob’s grandfather was imprisoned for four years.

Next to the interrogation room was a door fitted with its original soviet 1950’s security code system. This was the final stop on our tour: the ‘Spy Room’. Jacob explained that bugs were placed inside the guest’s rooms in the Jalta Hotel above, hidden within objects such as shoe brushes (which visitors were encouraged to take with them as a souvenir of their stay).

This bit of gear was state of the art in communist Czechoslovakia in the 1950s. And the 1980s.

Using the telephone-style exchange, the agents could select which of the hotel’s 94 rooms they wished to eavesdrop. If they could not understand the language of their targets, tape recorders could be employed to permit future translation. Above this equipment was a plan view of the hotel, with each room colour-coded. High importance intelligence targets from the West were coloured red, individuals of secondary importance yellow, and friendlies green.

Making our way back to the staircase and lifts, I thought about all the guests that had stayed in the Jalta over the decades, completely unaware of the bunker underneath the hotel. A goodly number of modern-day visitors, as they relax in the Hotel’s ground floor restaurant, may also not realise that a cold war remnant lies beneath their feet. It certainly was an experience entering a boutique hotel, and then taking a lift down into Czechoslovakia’s communist past. If you are visiting Prague, make sure to put this unique museum on your list.

Visit The Cold War Museum website here

If you enjoyed this post, you may also like Stasi Bunker Museum Machern, BunkArt 1

Leave a Reply