I crossed the Nisava River, after which the Serbian city of Nis is named, and headed north through steady drizzle. Another kilometre and I reached my destination: the foreboding walls of the Red Cross Concentration Camp. I followed the tall concrete until I reached the entrance gate, and stepped inside. Looking up the long path that lead to the large, grey, block-like building, I shuddered involuntarily. The silent, deserted place was chilling.

I walked up the wet concrete path, and upon reaching a small building, was met by a staff member. After paying for my admission, the lady guided me towards the large grey block. This structure and surrounding grounds was an old army facility, and was requisitioned by the Nazi occupation forces to create a concentration camp in September 1941.

‘By the order of the commander in charge you (the ‘respected citizens’ of Nis, which included members of political parties, civic associations, and the clergy) are being held as hostages. It is my duty to point out that this is not something we wished for. We are forced to act accordingly due to the crimes committed by your own bandits. Now your lives will be a gurantee for each and every German soldier, killed or wounded. By the count: 100 for a killed soldier, 50 for a wounded one.‘ Gestapo Commander in Nis, SS Captain Hammer

In addition to the hostages mentioned in the quote above, partisan fighters, Jewish and Romani people were also detained at the Red Cross Concentration Camp.

The first floor of the building included a large room, where straw had been placed to recreate, presumably, where prisoners slept.

The building was unheated, and I was glad of the many layers I was wearing. I couldn’t imagine what conditions in mid-winter must have been like for those imprisoned there.

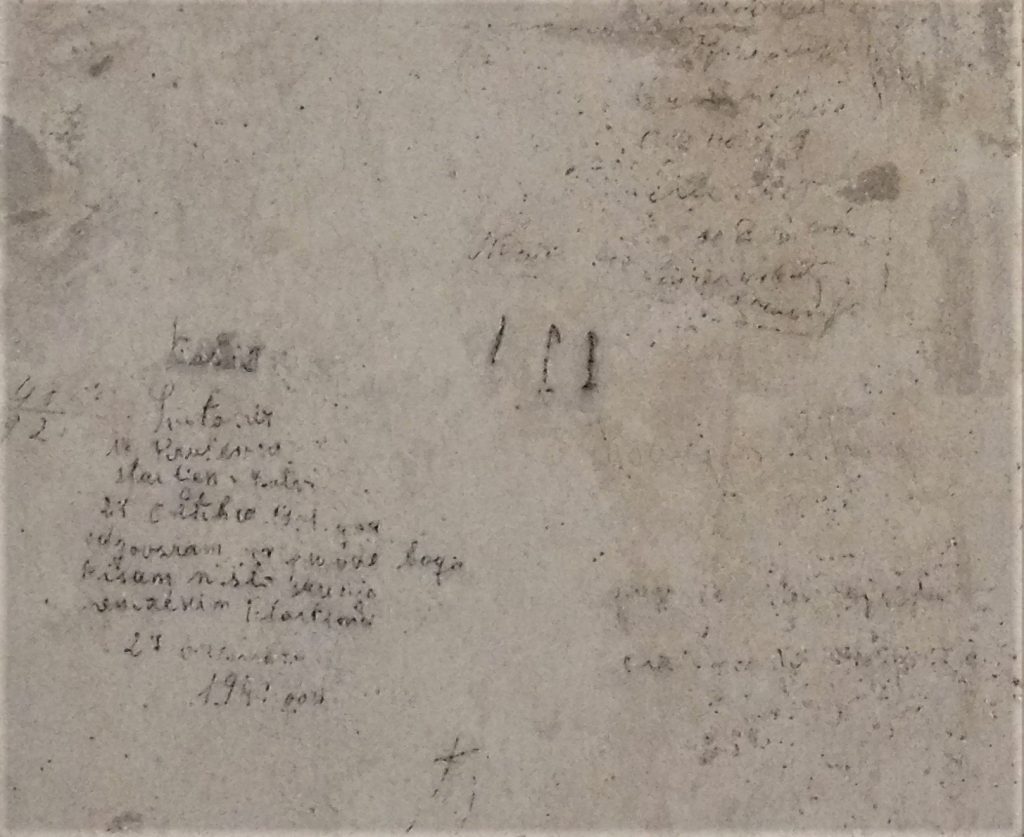

The handwritten word is a little like a fingerprint, and graffiti left on the walls of this room are a deeply personal link to those who were imprisoned within.

I walked up the flight of stairs to the second floor, acutely aware of being the only visitor, alone in the echoing, gloomy rooms. Displays explained the systematic rounding up of Jewish people from Nis and surrounding areas.

‘I remember the fate of a Jewish family from Zajecar…they were arrested and brought to the camp with four children…The girls wore long braids and we suggested to them to cut their hair short in order not to get lice. One of them said: ‘I cannot do it without the knowledge of my mum’. Dr Pijade suggested that they should ask their mother, who was allegedly in Belgrade…It was so touching to see all three of them sitting, and writing to their parents who had been shot a long time ago.’ Miroslava Savic

Mt Bubanj, about 3km south-west of Nis city centre, was chosen by the Nazis as the mass execution site for detainees sentenced to death. Murders were also carried out within the Red Cross Concentration Camp itself.

The museum displays included clothing and personal items taken from prisoners prior to execution, including these bow ties belonging to Jewish men.

Stories related the daily mistreatment of prisoners, from pointless physical labours used to weaken and humiliate, to casual brutality, systematic torture and summary execution.

After an hour of solitude, more visitors began to arrive at the museum. Some passed quickly through the exhibits; perhaps through disinterest, or an understandable unwillingness to engage more closely with the stories of suffering and death.

Two older ladies, who I thought may have been sisters, studied each of the displays carefully. Although I do not understand Serbian, they appeared to be discussing each information panel deeply, perhaps tracing the experiences of relatives, or that of other families known to them.

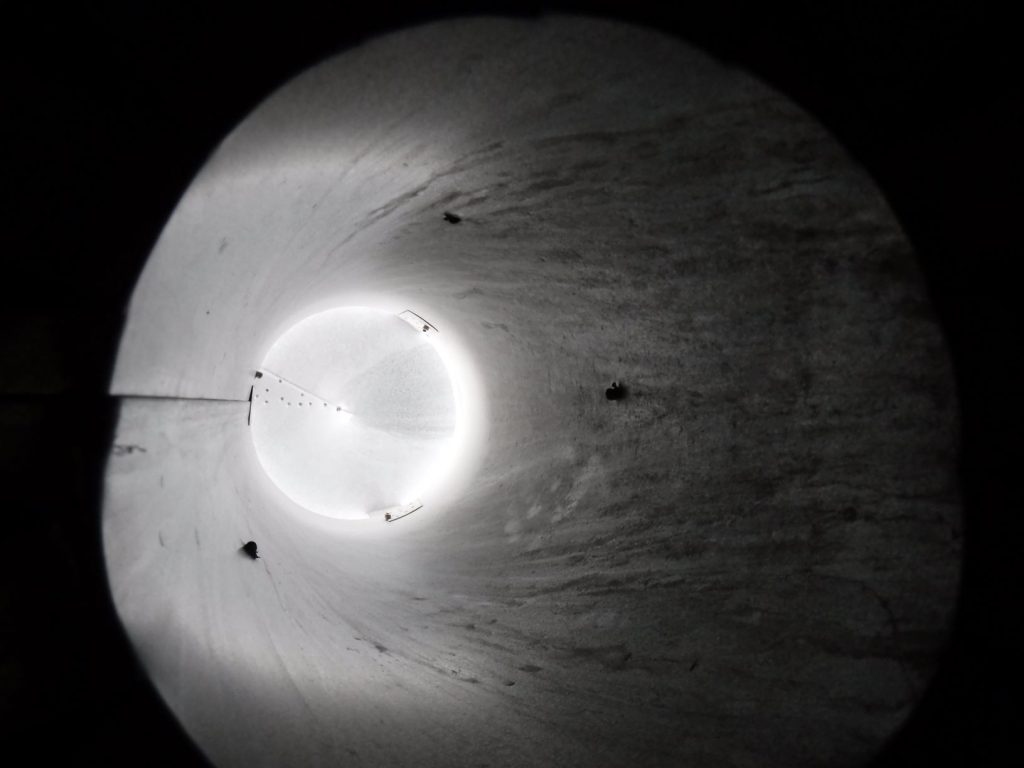

I followed the smooth concrete steps to the top floor, which was the attic space just below the roofline, where twenty solitary confinement cells had been built.

In the ceiling of the solitary confinement there was a small stovepipe through which a piece of the sky could be seen. That was the only connection with the outer world. Spending days like that in solitary confinement. I was shivering. Being exhausted (but) I could not fall asleep.‘ Nada Stanisavljevic

After spending time in a building that had witnessed so much suffering, I was relieved to descend the stairs and walk back into the outside air. The rain had stopped but the sky was leaden as I walked the stone paths of the camp grounds.

In several places, wreaths and the Serbian colours had been left in memory of the victims of the Red Cross Concentration Camp.

On some buildings, the faded paint of camp signs could still be seen, such as here on the guard house.

After spending some time walking through the camp, I made my way back down the concrete path to the gate. I was going to walk to Mt Bubanj; the same journey that thousands of people had made by truck when taken to the execution grounds by the Nazis in 1942-1944.

I shed my wet weather gear, as the rain had gone and the sky had begun to clear. About 45 minutes walk and I arrived, and began the climb along the avenue of leafless trees towards the hilltop. A spomenik (monument) of three towering fists dominates the memorial site. They differ in size, representing the men, woman and children who were murdered at Mt Bubanj.

Some Nis residents were making the most of the dry afternoon, gathering in groups within the amphitheatre which overlooks the monument. A couple of kids were kicking a soccer ball with their father beneath the symbols of defiance.

I walked up one of the pathways from the amphitheatre, then stepped a few metres into the forest. In the still and quiet of the late afternoon, it wasn’t hard to imagine the roar of the trucks, the shouts of the guards, and the crack of the shots that ended so many lives.

Visiting the Red Cross Concentration Camp was unsettling, confronting and heart-wrenching. Standing at Mt Bubanj on the site of murder on such a massive scale was a profoundly sad and humbling experience. The horror of this history is twofold; both the appalling suffering of the victims, and the knowledge that human beings are capable of such unspeakable cruelty.

Though they are not places for light-hearted holiday moments, ‘Dark Tourism’ locations play an important part in ensuring that such terrible events in our shared human history are never forgotten.

‘We were shot, but never killed. Never subdued. We crushed the darkness and paved the way for the sun.’

Ivan Vuckovic, Nis poet, enscribed at the memorial site at Mt Bubanj

If you liked this post you may also enjoy Strange Meeting, The Cemeteries of Gallipoli

Leave a Reply