I turned off the road onto the access track, which was covered in a layer of crisp brown pine needles. Pulling up in a clear spot under the trees I switched off the car. When I opened the door the sweet smell of pine flowed in thickly on the warm air, and cicadas screeched from the trees. It reminded me of December in Australia, of opening the front door of our old house, stepping in out of the heat and cicadas’ song, and being able to smell the pine Christmas Tree from where it stood in the living room.

I crunched across the desiccated needles, then followed the dirt track along the side of the cemetery, passing tall grasses with heavy seed heads that nodded in the light breeze. Thick prickly shrubs hid the graves from view until I turned the corner and approached the wooden gates. Carved into the sandstone block of the front wall of the cemetery was the name ‘Pink Farm’.

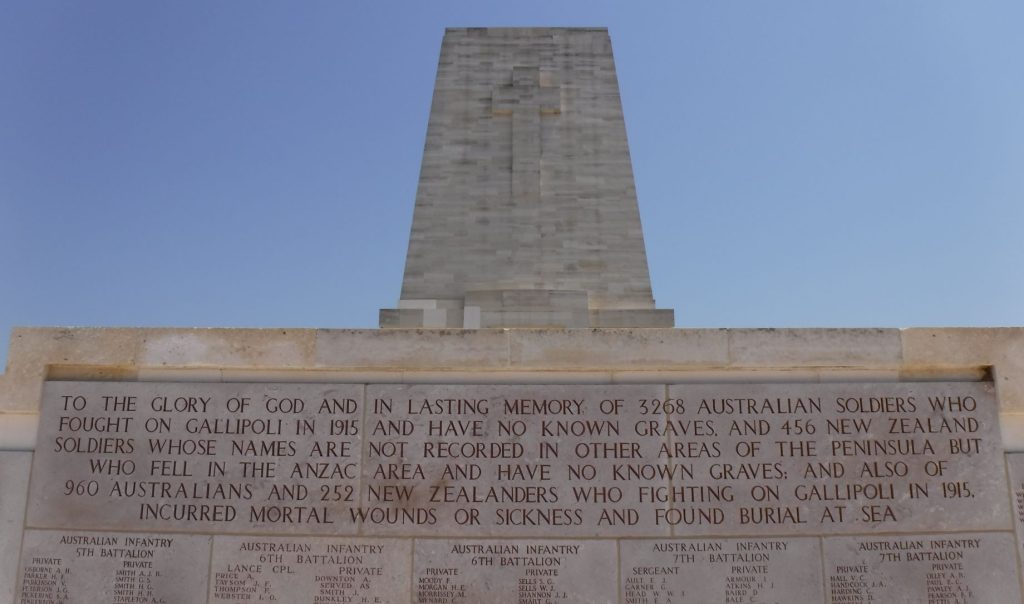

British forces landed on the southern tip of the Gallipoli Peninsula on 25 April 1915. Cemeteries were built for the soldiers killed in the fierce battles that followed, including several at Pink Farm, so named for the red soil of the area. After the Armistice in 1918, the burial grounds were consolidated into one cemetery.

Entering through the wooden gates, the dry, closely cut grass crackled under my feet, like the outfield of an Australian country cricket ground in summertime. The memorial headstones are laid out in neat rows, with rosemary, lavender and roses planted between them. Four trees shade the centre of the cemetery, and two white sandstone monuments, a feature of all the Commonwealth cemeteries, overlook the graves.

I am alone at Pink Farm with the 602 servicemen buried there, the majority of which were from the United Kingdom. The brutal nature of the conflict, and the inability to promptly recover the dead, made it impossible to identify many of those killed. ‘Believed to be buried in this cemetery’ is common on the headstones at Pink Farm, including that of Lance Corporal J. McKechnie who was 18 years old when killed on the 12th December 1915.

I have visited many of the cemeteries on the Gallipoli Peninsula, some of which are located in rolling farmland, others overlook the Aegean, or lie on the sites of major battles.

When I arrived at Shell Green Cemetery, a Turkish maintenance crew from the Commonwealth War Graves Commission was working amongst the headstones. There were a couple of gardeners, and other blokes carefully brushing the headstones and using a variety of tools to clean the engravings.

The Gallipoli cemeteries are kept immaculately. Using my phone to translate, I thanked two of them in Turkish for taking care of the Australians. One smiled and gave me a thumbs up, and the other nodded and said ‘tesekkurler’ (thankyou).

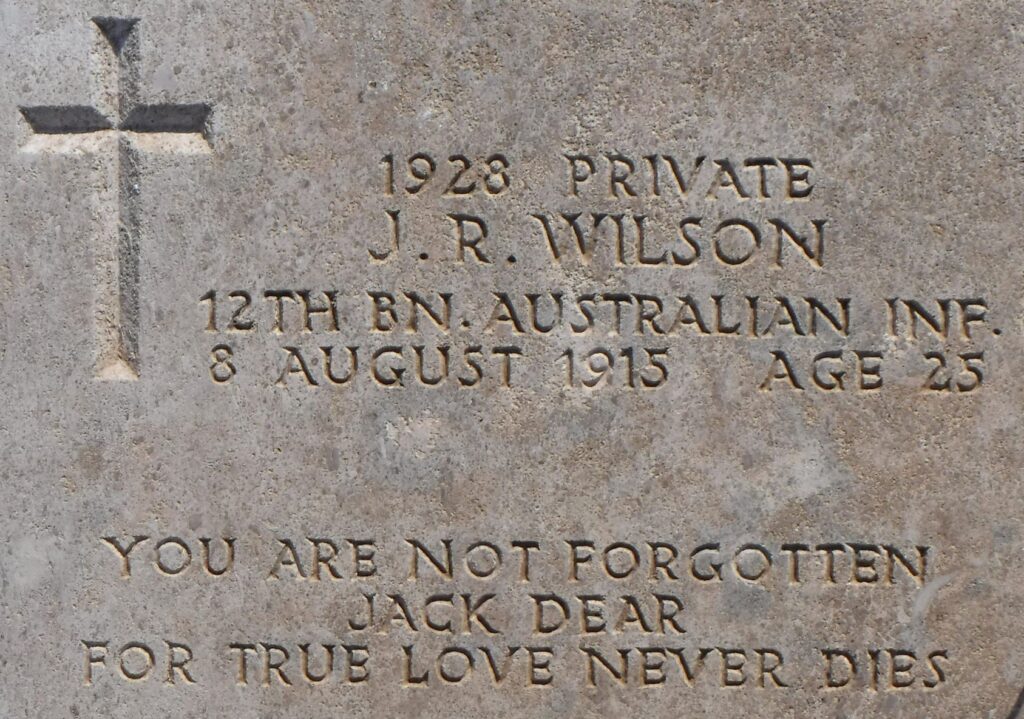

Amongst the 409 burials at Shell Green Cemetery is John Robert Wilson, a miner from Broken Hill, New South Wales.

When I pulled into the carpark of the Lone Pine Cemetery it was empty. After walking the rows of memorial headstones for a while, I noticed two older men and a little girl had arrived at the other end of the cemetery. The two men, a grandfather and great uncle perhaps, were walking either side of the girl, who had her tiny arms outstretched and was holding their hands. After spending some time at the memorial, they made their way across the length of the cemetery to where I was standing. They approached, and one of the old men greeted me, and asked where I was from. When I answered he said, ‘Ahhh…Australia. Welcome.’ The other gentleman put his hand across his heart and bowed his head (‘I am honoured to meet you’).

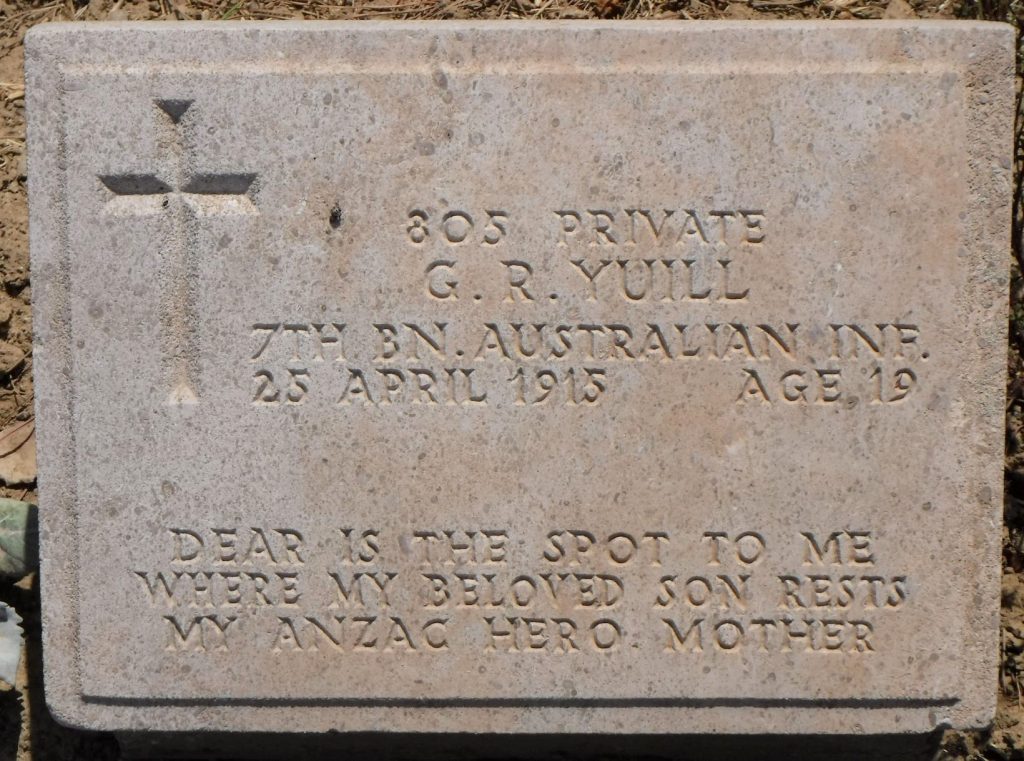

The ‘lonesome pine’, a single tree standing where the ANZACs and Turkish forces faced off in this part of the front, was soon destroyed in the fighting. A pine cone sent back to Australia from the battlefield provided the seed for the Lone Pine now standing at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra. It was a seed from this tree that was taken back to Gallipoli and planted in the Lone Pine Cemetery. The tree now provides a cool shady place amongst the 670 casualties interred there, which include George Yuill, a miner from Eaglehawk, Victoria.

Also commemorated at Lone Pine is the youngest ANZAC to lose his life at Gallipoli. The majority of the Allied troops who landed on the Peninsula were young men, however others were just boys. After spending six weeks on the Peninsula stationed at Courtney’s Post, Private James Martin from Tocumwal, New South Wales died from illness on October 25th, 1915, aged 14 and nine months. Buried at Sea, Private Martin is listed on Lone Pine’s memorial.

Recounting his near-death experience at Dead Man’s Ridge, Private Thomas Baker (Chatham Battalion, Royal Marine Brigade, Royal Naval Division), who like so many others at Gallipoli was not yet twenty years of age, stated ‘When I saw those bullets coming along, I knew that would be the end of me if they came along far enough… They say your past comes up, but I can say truthfully that I hadn’t got much past at nineteen…’

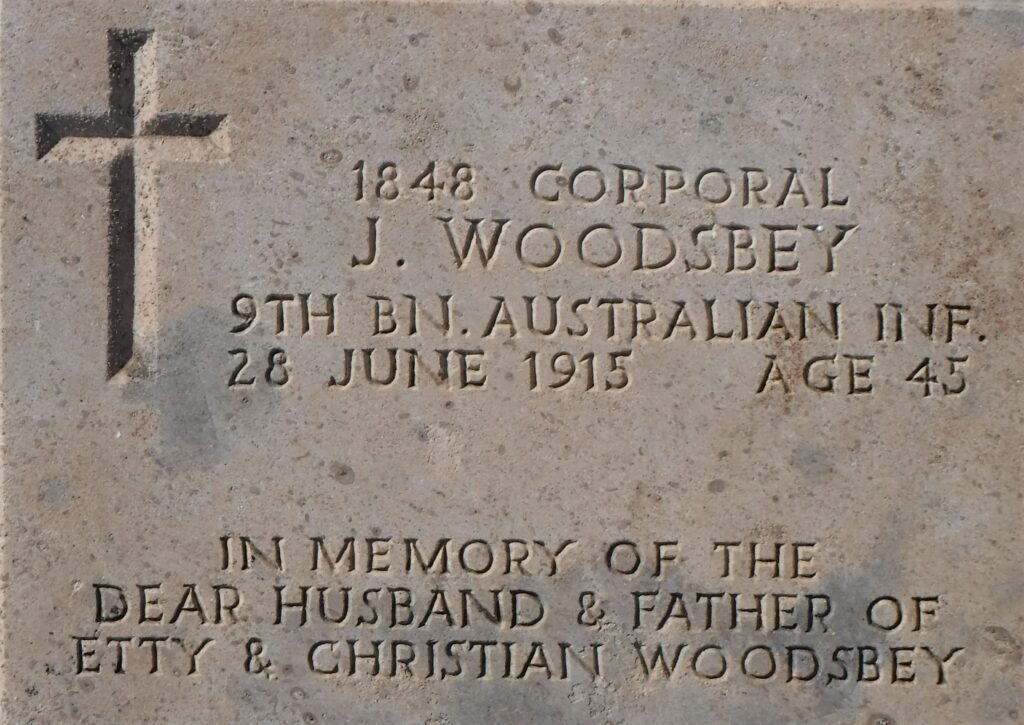

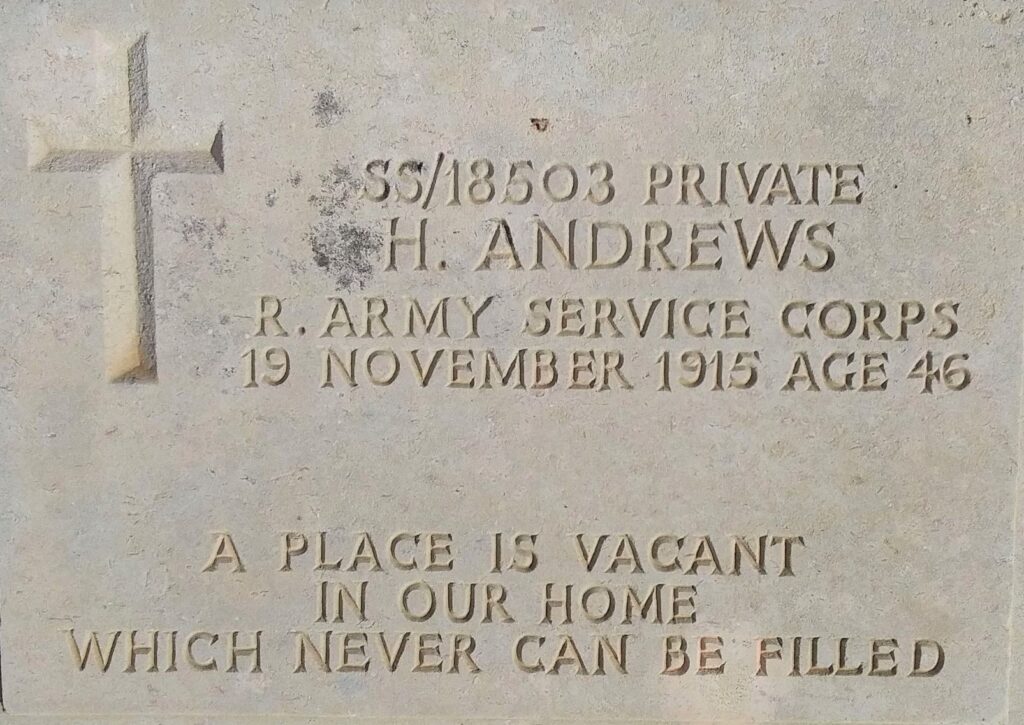

The Gallipoli cemeteries also hold middle-aged men, like Corporal Joseph Woodsby, from Rockhampton, Queensland, who is buried at Shell Green, and Private H. Andrews who was 46 when he died, and lies in Ari Burnu Cemetery.

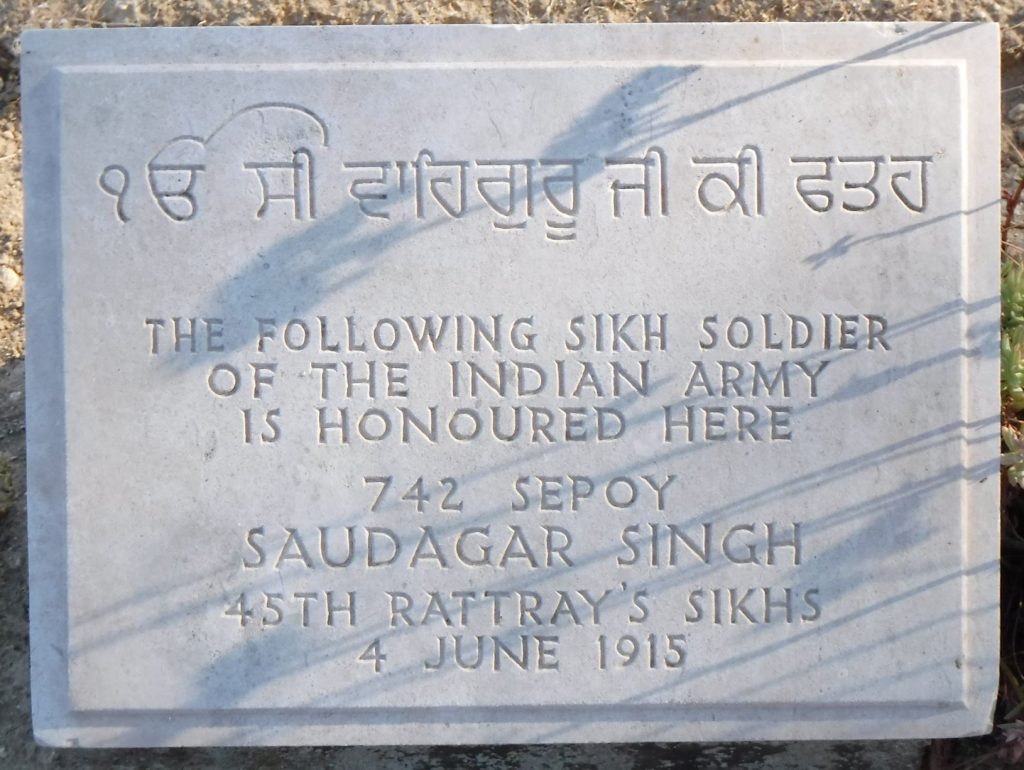

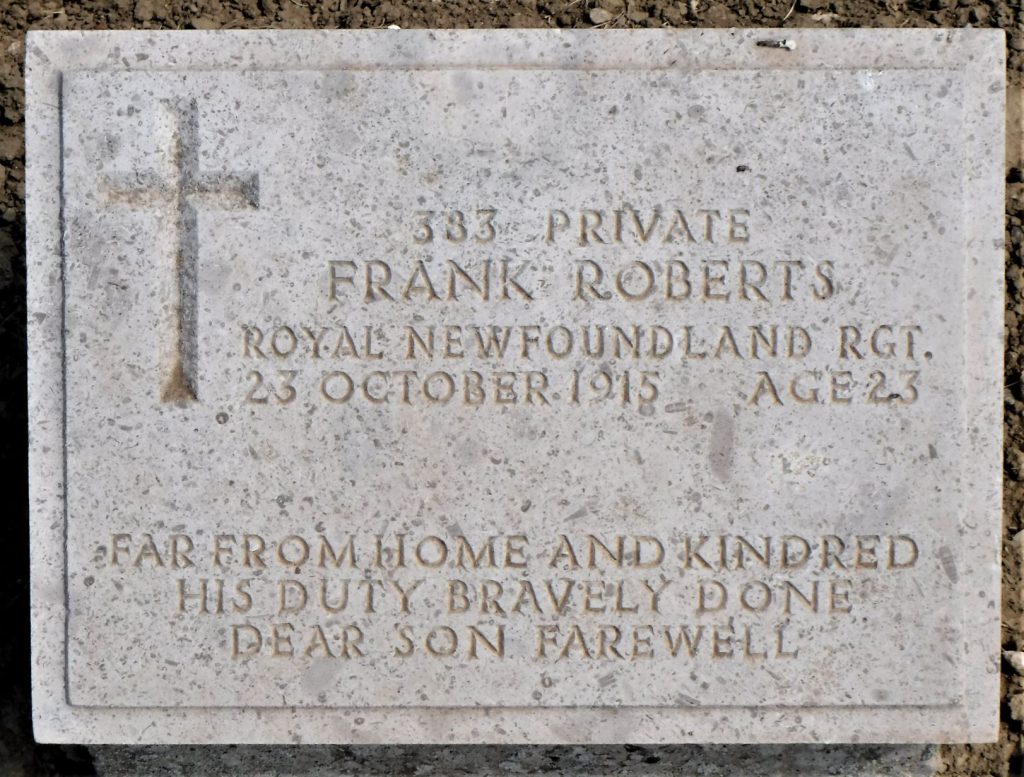

Many nationalities fought with the Allies and died at Gallipoli. Saudagar Singh is buried at Redoubt Cemetery, whilst members of the Newfoundland Regiment (raised in what is now Canada), including Private Frank Roberts, lie at Hill 10.

A Turkish friend took the day off work to join me on one of the days I visited the Gallipoli cemeteries. It was fascinating to have the Turkish perspective on the conflict as we went from site to site in the hills behind ANZAC Cove. Some of the Allied headstones featured the epitaph dulce et decorum est pro patria mori ‘it is sweet and fitting to die for one’s country’. Both Ilker and I agreed that rather than having to sacrifice yourself, it would be far better to die in your home as an old man surrounded by your family.

Turkish cemeteries are found across the southern Peninsula. Some, like the Canakkale Martyrs’ Memorial, are part of large commemorative sites which include statues and monuments. Headstones at the Martyrs’ Memorial cemetery list the names of casualties according to their home town or district. Others cemeteries are found at the end of walking tracks; quiet places were the names of the dead are engraved in steel. I visited Gallipoli during the summer school holidays, and the Turkish cemeteries were bustling with families and tour groups.

At Soganlidere Martyrs’ Cemetery, commemorative headstones take the form of Turkish soldiers’ helmets, and the words of the Turkish national poet Mehmet Akif Ersoy are engraved on the memorial.

The French Cemetery, with its lines of black steel crosses, is located above Morto Bay, on the south-eastern point of the Gallipoli Peninsula. It contains 2,240 known servicemen, and at the highest point of the cemetery are a number of monuments, including four large, white rectangular blocks. Each marks the place where 3000 unknown French soldiers are interred.

Although numbers are not my strong point, visiting the cemeteries at Gallipoli got me thinking. I read somewhere that the average age of ANZAC soldiers at Gallipoli was 28. To be conservative I’ll round it up to 30. I’ll also assume that the British, French and other allied forces averaged the same. I took a sample of the ages of fallen Turkish soldiers listed at Canakkale Martyrs’ Memorial, the average of which also came out at 28 years. Again, for the sake of the exercise, I’ll round this figure up to 30.

Numbers vary, but estimates of 44,072 Allied soldiers killed, and 86,692 Turkish, totals a staggering 130,764 lives. Assuming that an Allied soldier who avoided death at Gallipoli would have lived to a conservatively estimated 60 years old, then each one that was killed lost 30 years of life. Perhaps the average age of natural death for a surviving Turkish soldier would have been a little less, again being conservative I’ll say 55, meaning that each soldier killed lost 25 years. Tallying it up, a total of 3,489,460 years of life were lost as a consequence of the nearly 11 months that World War I raged on the Gallipoli Peninsula. Nearly 3.5 million years lost from individuals, their families, communities and nations.

The days are long during the Turkish summer, and the evening air is still warm at Pink Farm as the sun begins to settle over the island of Gokceada. Returning to the entrance, I swing the little wooden gate closed and fasten the latch. I leave behind the 602 souls buried at Pink Farm, with their neat gardens, lines of headstones, and epitaphs both ‘standard’ and heart-breakingly personal. The cemeteries of Gallipoli hold tens of thousands who died in 1915; every one a story of a life cut short by the tragedy that occurred here in this beautiful place.

Lest we forget.

For more information visit the Australian War Memorial

If you enjoyed this post, you may also like Visiting Gallipoli, HMS Lundy and HMS Louis

Leave a Reply