‘I ordered the immediate expansion of our western fortifications. I can assure you that since May 28, the most gigantic fortifications of all time have been under construction there.’ Adolf Hitler, Nazi Part rally in Nuremberg, 1938.

I had traveled to the small town of Pirmasens in Rhineland-Palatinate to visit a Ukrainian friend of mine. She, like many other displaced Ukrainians, has found refuge in Germany whilst waiting for peace to return to her country. At the closest point, Pirmasens is only about 10km from the French border, and is on the edge of Germany’s largest forested area. It’s a pretty town, and I looked forward to spending a few days there catching up with my friend, and exploring the district.

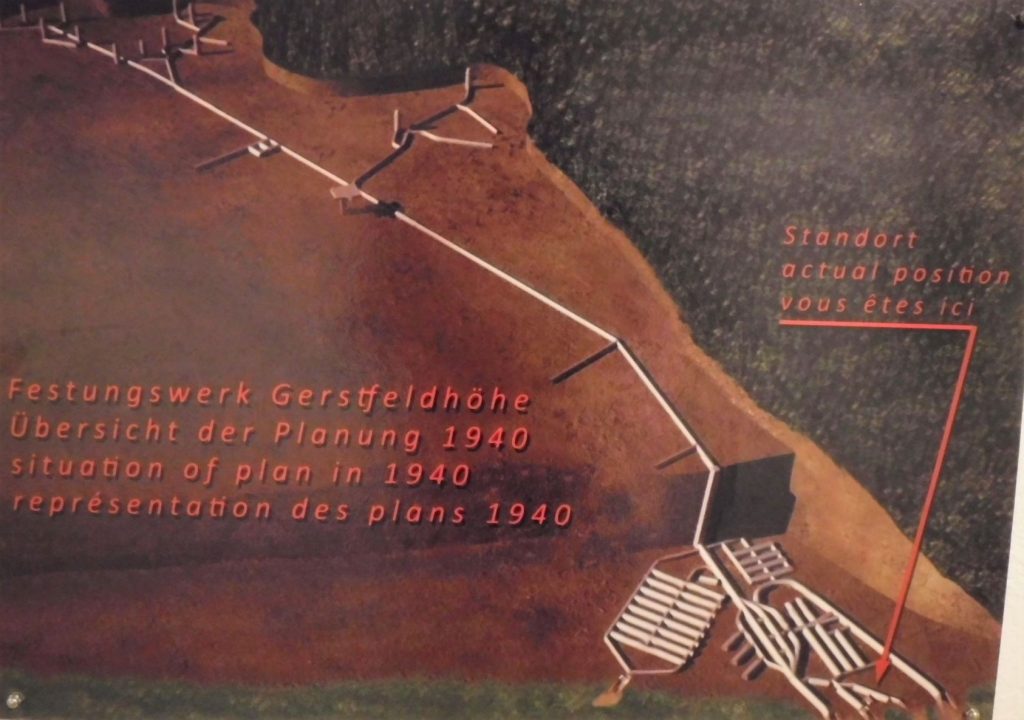

Whilst doing a little research into things to see in the area, I found out that one of the 1930’s-era Westwall bunkers was located on the edge of town, and had been opened as a museum. The Westwall, known as the ‘Siegfreid Line’ to the Allies, was Hitler’s reinforced defensive line which stretched from the Dutch border along Germany’s western boundary to Switzerland. lt comprised large underground reinforced bunker systems, smaller concrete pillboxes, lines of tanks traps, anti-tank ‘moats’, minefields and barbed wire. The Museum is housed within the Gerstfeldhöhe Fortress, a ‘key defensive installation of the Westall’1. One Saturday afternoon I walked the 45 minutes from my apartment to check it out.

The signage to the Museum was adequate but low-key, and when I turned up the final access road and reached the small carpark, the entrance was similarly understated. A couple of post-WWII era tanks sat off to one side, and a number of small concrete structures and a tank turret could be seen in the surrounding scrub.

At the foot of the dark, forested slope was a concrete entranceway, providing little indication as to what lay beyond.

It was a warm summer’s day, and I had worked up a sweat by the time I heaved open the heavy door to the Museum. I stepped into the cool of the bunker, where I reckon the temperature must have been about 12 degrees. I was pleased for the relief from the after my hot walk, at least initially. After passing through a second ‘airlock’ door, I walked up the narrow passage to the ticket office and paid for entry.

Entering military bunkers is like stepping into a hidden underground world, probably because that is exactly what you are doing. I hadn’t done much research into the Westwall Museum at Pirmasens, so I didn’t really know what to expect. Consequently, despite only part of the original structure being open to the public, I found the scale of the complex staggering.

At the end of the entrance hall was the first line of defense against a penetrative attack on the fortress.

Walking deeper into the bunker, it wasn’t long before the cool air started to chill me.

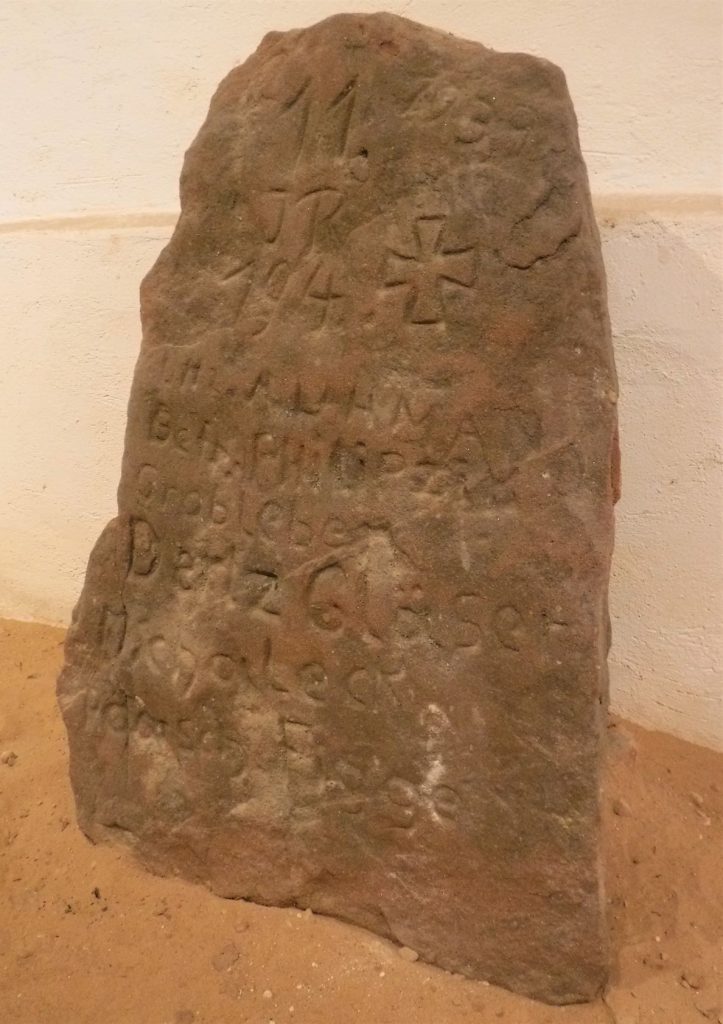

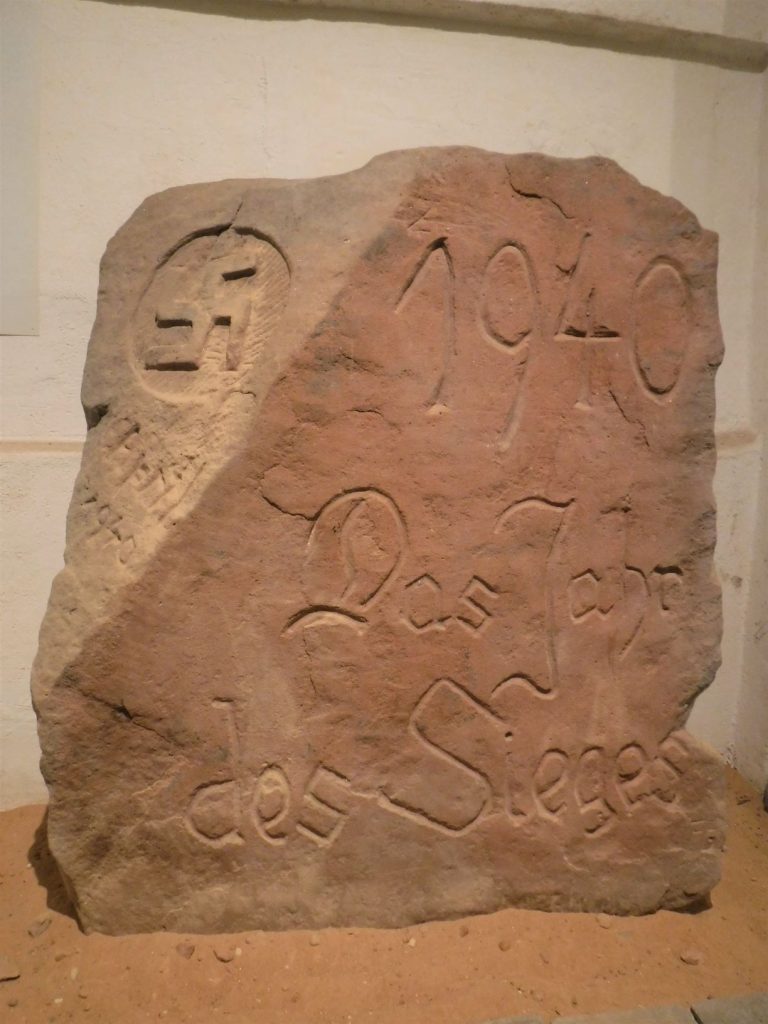

A display of two large engraved blocks of Rhineland sandstone provided a tangible link to the soldiers stationed at the Fortress.

This block reads ’11 IR 194′ and the date ‘1939’. The Museum explains that member of ’11 Company, Infantry Regiment 194′ stationed at Gerstfeldhöhe Fortress in 1939 are likely to have carved the title and added their names to the stone.

‘1940, The Year of Victory’. According to the Museum, this monument celebrates the German conquest of France. The Westwall, although not having been directly involved in the fighting, had provided a deterrent to French attack during the first 8 months of the war.

Moving beyond the sandstone carvings, and a gallery of paintings and photographs dotted with mould from the damp and cool interior, the passageway made a turn to the right. I followed the bend, and entered a tunnel that seemed to go on forever.

I had arrived in the longest preserved tunnel within the complex, which traveled deep into the hillside.

Military vehicles and assorted World War II relics were displayed along the length of the tunnel.

German half-track Sd.Kfz 251

By the time I reached the end of the long passageway, the cold was starting really starting to gnaw. Beyond this door, not accessible to the public, an elevator shaft ran up to a line of more shallow defenses beyond.

At several points along the marked route through the labyrinth of tunnels, unlined rough-hewn passageways lead into the darkness.

In 1944/45, the defensive capabilities of the Westwall were tested as the advancing Allies pushed on into Germany. The Gerstfeldhöhe Fortress, however, never saw action, although local civilians took shelter within the bunker during air raids. After World War II, the US Army used the Gerstfeldhöhe Fortress as a storage area.1

After touring the Westwall’s Museum at my typically glacial pace, I was freezing by the time I eventually emerged into the late afternoon sun. I later found out from the Museum’s website that the bunker has a constant temperature of 8 degrees celcius, so my estimate of 12 degrees had been a little generous. The Museum was far bigger and more comprehensive than I had expected, and I really enjoyed exploring the complex.

The following day I picked up a hire car in order to explore the area around Pirmasens. The Museum had fuelled my interest to see more relics of the Westwall, so I traveled to the small village of Steinfeld.

Starting on the edge of town, the ‘Westwall Wanderweg’ walking trail visits a number of Westwall features in the district. With a cornfield on one side, I walked along the narrow track beside what looked like a natural watercourse. Ducks paddled around in the water, and locals walking their dogs bid me a cheerful ‘Morgan! (morning)’. The waterway was, in fact, part of the Westwall: an anti-tank ditch created to block the progress of Allied vehicles.

An information sign near the flooded ‘moat’ explained that it was favoured over other types of built defensive structures due to ‘unfavourable soil conditions’, presumably as the area was swampy. Built in 1938, the ditch is 940 metres long, 35 metres wide and 3.5 metres deep.

Today, the waterway is a place of recreation and biodiversity conservation.

Crossing the railway line and heading back into town, I arrived at a broad line of ‘dragon’s teeth’. These steel reinforced, concrete triangles were used extensively along the Westwall defensive line. The ‘teeth’ are small on the enemy side, encouraging tanks to attempt to cross the obstacle, whereupon they become stuck on the increasingly larger triangles.

I followed along the line, which ran for several hundred metres. Just off the road, some had been removed to allow vehicle access to a property.

Tangles of blackberries and ivy had overgrown the obstacles in part, and the branches of orchard trees leaned over residents’ boundary fences. I plucked and ate blackberries as I explored the line, which at one point turned towards town and ran between the residents’ houses.

On this warm and peaceful summer’s morning, one old bloke was tending to his garden right beside the dragon’s teeth. He ignored me, probably well accustomed to tourists wandering past his back fence. His neighbour seemed a little sensitive to visitors, as I found a note on my windscreen when I got back to the car telling me that I had parked on private property.

Visiting a few of the Westwall sites had been a fascinating experience. The Westwall Museum felt a little like stepping into a time capsule, and seeing remnants of the Wall around Steinfeld gave some perspective of the scope of the defenses. There appears to be a strong committment by local people to preserve what is left of the Westwall; a stark and solemn reminder of the dark days of World War II.

1 McNab, C. (ed) 2014, ‘Hitler’s Fortresses – German Fortifications and Defences 1939-45’, Osprey Publishing

Visit the Westwall Museum Pirmasens here

If you enjoyed this post, you may also like Stasi Bunker Museum, Machern; Repurposing Albania’s Nuclear Bunkers Part I

Leave a Reply